Wait a second, read that title again. This isn’t a throwback 3D printing project at all. That’s “RepTrap” as in reptile trap, and it’s a pretty clever way to study our cold-blooded friends in their natural habitat.

Now, game cameras — or trail cameras, if you’re less interested in eating what you see — are pretty much reduced to practice. For not that much money you can pick up one of these battery-powered devices, strap it to a tree, and have it automatically snap high-quality pictures of whatever wildlife happens to wander past. But nearly all of the commercially available game cameras have pyroelectric infrared sensors, which trigger on the temperature difference between a warm-blooded animal and the ambient temperature of the background. But what to do when you’re more interested in cold-blooded critters?

Enter [Mirko], who stumbled upon this problem while working with a conservation group in Peru. The group wanted to study snakes, insects, and other ectothermic animals, which are traditionally studied by trapping with pitfalls and other invasive techniques. Unable to rely on PIR, [Mirko] rigged up what amounts to a battery-powered light curtain using a VL53L4CD laser time-of-flight sensor. Mounted above the likely path of an animal, the sensor monitors the height of everything in its field of view. When an animal comes along, cold-blooded or otherwise, RepTrap triggers a remote camera and snaps a picture. Based on the brief video below, it’s pretty sensitive, too.

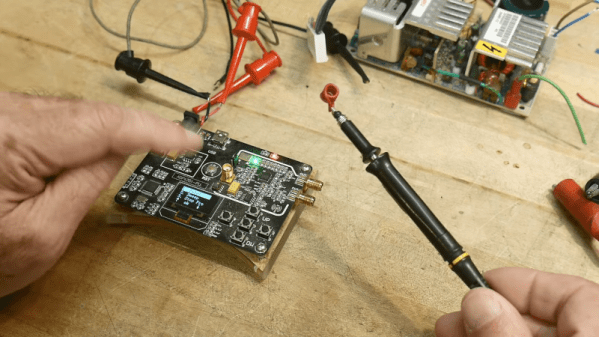

[Mirko] started out this project using an RP2040 but switched to an ESP32 to take advantage of Bluetooth camera triggering. The need for weatherproofing was also a big driver for the build; [Mirko] is shooting for an IP68 rating, which led to his interesting use of a Hall sensor and external magnet as a power switch.

Continue reading “RepTrap Keeps Watch Over Our Cold-Blooded Friends”

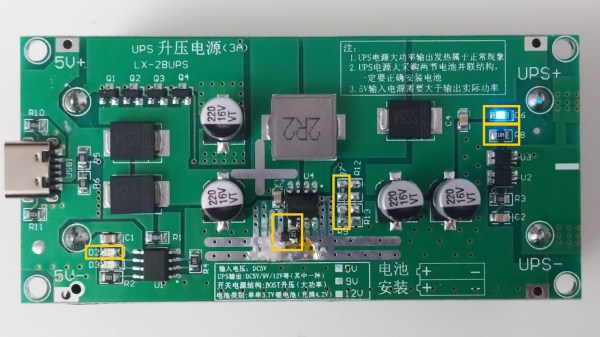

![The patched up XR2981 boost IC with MCP809 reset IC installed. (Credit: [MisterHW])](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/upload_34f9a5c70d7738a67185359c3110505b.jpg?w=400)