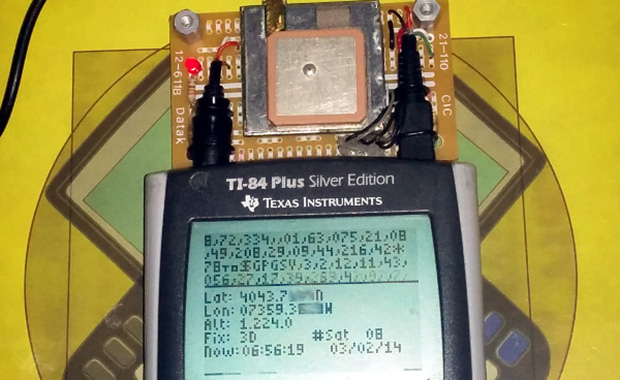

[Chris], graphing calculator hacker extrordinaire, has seen a few of his projects show up on the front page of Hackaday, mostly involving builds that turn graphing calculators like the TI-84 Plus shown above into something that copies a few features from a smartphone. His latest build, a hardware GPS module attached to the TI-84 Plus, is yet another feather in his cap of awesome and impractical addition to a classic piece of hardware.

[Chris], graphing calculator hacker extrordinaire, has seen a few of his projects show up on the front page of Hackaday, mostly involving builds that turn graphing calculators like the TI-84 Plus shown above into something that copies a few features from a smartphone. His latest build, a hardware GPS module attached to the TI-84 Plus, is yet another feather in his cap of awesome and impractical addition to a classic piece of hardware.

There were two major technical challenges behind adding GPS to a graphing calculator. The first of these was powering a GPS sensor. Many a calculator modder has put a lot of work into documenting the USB port on the 84 Plus, revealing it is a USB OTG port, capable of serving as a host or device. It also supplies 5V of power to just about anything, burning through batteries as a result.

The next challenge was reading the data coming off the GPS sensor at 4800bps.The TI-84 Plus series of calculators have a series of interrupts that can fire at fractions of the 15MHz clock. By setting the timer up to fire every 197 clock ticks and dividing again by 16, [Chris] can read data at 4758.9bps. It’s close enough to get most of the data, and the checksum included in the NMEA protocol allows the software to discard bad messages.