Everybody needs an external USB drive at some time or another. If you’re looking for something with the nerd cred you so desperately need, build a 5 1/4″ half height external drive. That’s a mod to an old Quantum Bigfoot drive, and also serves as a pretty good teardown video for this piece of old tech.

The Woxun KG-UV2D and KG-UV3D are pretty good radios, but a lot of amateur radio operators have found these little handheld radios eventually wear out. The faulty part is always a 24C64 Flash chip, and [Shane] is here to show you the repair.

Last year there was a hackathon to build a breast pump that doesn’t suck in both the literal and figurative sense. The winner of the hackathon created a compression-based pump that is completely different from the traditional suction-based mechanism. Now they’re ready for clinical trials, and that means money. A lot of money. For that, they’re turning to Kickstarter.

What you really need is head mounted controls for Battlefield 4. According to [outgoingbot] it’s a hacked Dualshock 4 controller taped to a bike helmet. The helmet-mounted controller has a few leads going to another Dualshock 4 controller with analog sticks. This video starts off by showing the setup.

[Jan] built a modeling MIDI synth around a tiny 8-pin ARM microcontroller. Despite the low part count, it sounds pretty good. Now he’s turned his attention to the Arduino. This is a much harder programming problem, but it’s still possible to build a good synth with no DAC or PWM.

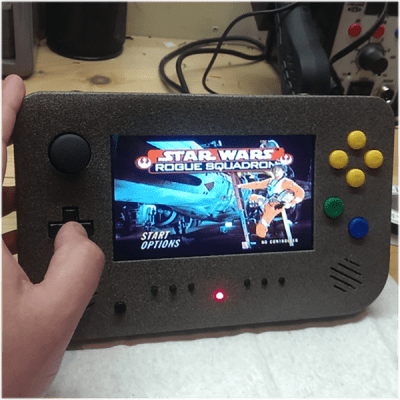

The enclosure for this project was initially printed in PLA, the parts glued together and finally filled for a nice, smooth finish. [Chris] says PLA was a bad choice – the low melting point means the heat from milling the face plate gums up the piece. In the future, he’ll still be using printed parts for enclosures, but for precision work he’ll move over to milling polystyrene sheets.

The enclosure for this project was initially printed in PLA, the parts glued together and finally filled for a nice, smooth finish. [Chris] says PLA was a bad choice – the low melting point means the heat from milling the face plate gums up the piece. In the future, he’ll still be using printed parts for enclosures, but for precision work he’ll move over to milling polystyrene sheets.