The time to enter The Hackaday Prize has ended, but that doesn’t mean we’re done with the world’s greatest hardware competition just yet. Over the past few months, we’ve gotten a sneak peek at over a thousand amazing projects, from Open Hardware to Human Computer Interfaces. This is a contest, though, and to decide the winner, we’re tapping some of the greats in the hardware world to judge these astonishing projects.

Below are just a preview of the judges in this year’s Hackaday Prize. We’re sending the judging sheets out to them, tallying the results, and in less than two weeks we’ll announce the winners of the Hackaday Prize at the Hackaday Superconference in Pasadena. This is not an event to be missed — not only are we going to hear some fantastic technical talks from the hardware greats, but we’re also going to see who will walk away with the Grand Prize of $50,000.

Mitch Altman

Mitch Altman

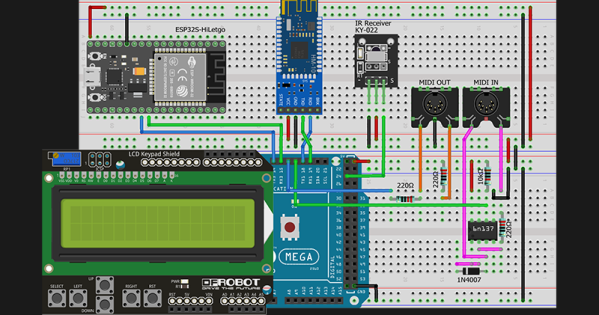

Mitch’s early claim to fame is inventing the TV-B-Gone, a device that is so devious it got several Gizmodo reporters banned from CES for life. I suppose the idea was to punish those Gizmodo reporters, but as we all know being banned from CES is a blessing in disguise. Mitch has been published in Make Magazine, 2600, and is a mentor at the HAX accelerator. He is the co-founder of Noisebridge, the legendary San Francisco hackerspace, president and CEO of Cornfield Electronics, and makes his way around to various hacker gatherings where he’s always more than eager to teach people the ins and outs of electronics, soldering, and teaching cool things.

Chris from Clickspring

Chris from Clickspring

Clickspring, or Chris as he’s called by people IRL, has made his mark by being one of the best machinist channels on YouTube. Chris began making videos several years ago by recreating a brass clock in his home machine shop. Over the course of several months and millions of views on YouTube, Chris delved deep into the technology of making a clock out of brass stock using the most minimal machine tools. Currently, Chris is working on a multi-part video series where he’s constructing a replica of the Antikythera Mechanism using only technology that would have been available to a Greek engineer around the year 100 BC. This is, simply, one of the greatest feats of experimental archaeology, and it’s happening right now on Chris’ YouTube channel.

Kristin Paget

Kristin Paget

Kristin ‘Hacker Princess’ Paget is currently working at Lyft designing security systems for self-driving cars and futzing about with wireless security. For fun, she builds IMSI catchers and RFID cloners, and has given talks at the Hackaday Superconference about the laws of IoT Security and at Shmoocon about how terrible contactless credit cards actually are. When it comes to wireless security, Kristin is who you want to talk to, and she was instrumental in getting the FBI off my back that one time.

Ayah Bdeir

Ayah Bdeir

Ayah Bdier is the founder and CEO of littleBits, an award-winning platform of easy-to-use electronic building blocks that are empowering kids everywhere to create inventions large and small. Bdeir is an engineer, interactive artist, and one of the cofounders of the Open Hardware Summit. An alumna of the MIT Media Lab, Bdeir was named a TED Senior Fellow in 2013. She’s been featured on CNBC for building the future with next-generation toys, and talking about the importance of providing children with educational and gender-neutral toys.

These are just a few of the amazingly accomplished judges we have lined up to determine the winner of this year’s Hackaday Prize. The winner will be announced on November 3rd at the Hackaday Superconference. There are still tickets available, but if you can’t make it, don’t worry. We’re going to be live streaming everything, including the prize ceremony, where one team will walk away with the grand prize of $50,000. It’s not an event to miss.