[Vintage Backyard RC] has built a nice little RC track in his backyard, and wanted a motorized dolly system to capture footage along the main straight with his GoPro. Using only junk box parts, he created a simple pedal operated RC cable dolly. (Video, embedded below.)

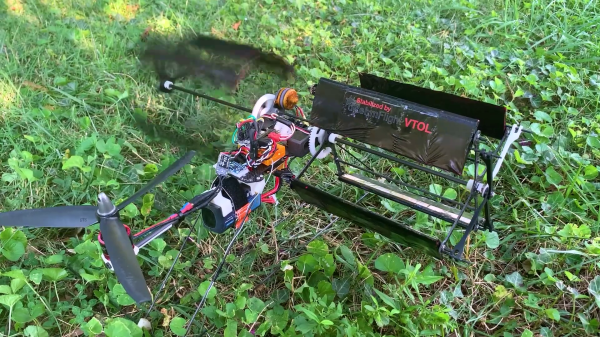

[Vintage Backyard RC] first experimented with a high speed car running on a length of model train track. However, it was bumpy at high speed, the track is expensive, and it needs 50 V running through the open tracks. The new cable cam gives a much smoother ride, and cost almost nothing with his supply of old RC gear. The cable cam is powered by a brushed motor from an RC airplane, running with plastic wheels on some weed trimmer line. Control is provided by an old 27 MHz RC system, with the controller’s internals transplanted into an old wah-wah guitar pedal.

The non-geared motor can drive the cable much faster than required, so [Vintage Backyard RC] needs to exercise some careful foot control to run it at a reasonable speed. This is easier said than done while also controlling an RC car with his hands, so he plans to replace the RC system with a newer 2.4 GHz system software end-point limits. We would be reaching for the ESP32 or any other microcontroller with wireless that we’ve come to know, but it’s worth remembering that most people are not familiar with these tools.

This is definitely the most minimalist cable cam we’ve covered this year, but just demonstrates how simple they can be to build. You can always upgrade to a sleek folding frame from 3D printed parts, and add machine vision and long range video streaming.

Continue reading “Pedal Operated Cable Cam For Hands Free Video”