The demoscene never ceases to amaze. Back in the mid-80s, people wouldn’t just hack software to remove the copy restrictions, but would go the extra mile and add some fun artwork and greetz. Over the ensuing decade the artform broke away from the cracks entirely, and the elite hackers were making electronic music with amazing accompanying graphics to simply show off.

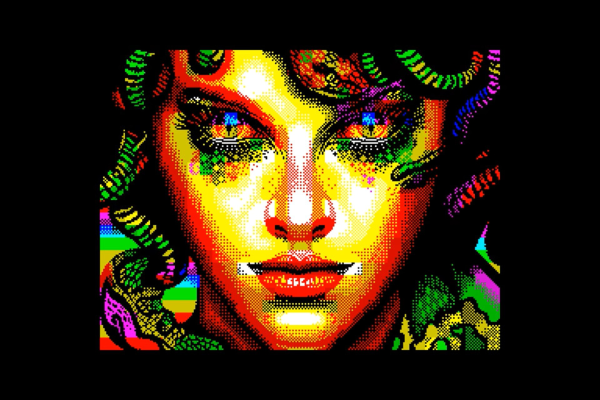

Looked at from today, some of the demos are amazing given that they were done on such primitive hardware, but those were the cutting edge home computers at the time. I don’t know what today’s equivalent is, with CGI-powered blockbusters running in mainstream cinemas, the state of the art in graphics has moved on quite a bit. But the state of the old art doesn’t rest either. I’ve just seen the most amazing demo on a ZX Spectrum.

Simply put, this demo does things in 2022 on a computer from 1982 that were literally impossible at the time. Not because the hardware was different – this is using retro gear after all – but because the state of our communal knowledge has changed so dramatically over the last 40 years. What makes 2020s demos more amazing than their 1990s equivalents is that we’ve learned, discovered, and shared enough new tricks with each other that we can do what was previously impossible. Not because of silicon tech, but because of the wetware. (And maybe I shouldn’t underestimate the impact of today’s coding environments and other tooling.)

Simply put, this demo does things in 2022 on a computer from 1982 that were literally impossible at the time. Not because the hardware was different – this is using retro gear after all – but because the state of our communal knowledge has changed so dramatically over the last 40 years. What makes 2020s demos more amazing than their 1990s equivalents is that we’ve learned, discovered, and shared enough new tricks with each other that we can do what was previously impossible. Not because of silicon tech, but because of the wetware. (And maybe I shouldn’t underestimate the impact of today’s coding environments and other tooling.)

I love the old demoscene, probably for nostalgia reasons, but I love the new demoscene because it shows us how far we’ve come. That, and it’s almost like reverse time-travel, taking today’s knowledge and pushing it back into gear of the past.