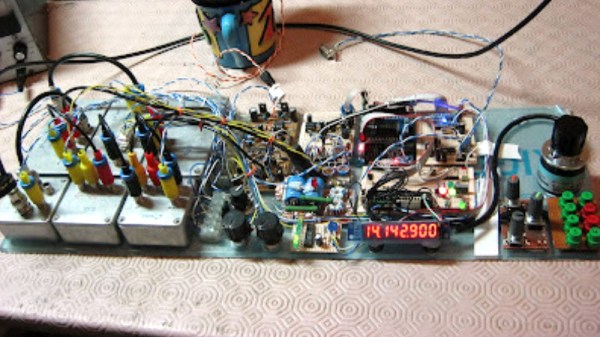

We will have all at some point seen a fascinating project online, only to find not enough information to really appreciate and understand it. Such a project came [Bill Meara]’s way over at the SolderSmoke podcast, and he was fortunately able to glean more from its creator. What [Tom] had made from junkbox parts was a fairly traditional analogue receiver for the 20m amateur band which would be quite an achievement in itself, but what makes it special is its use of an FPGA to augment the analogue tuning.

A traditional analogue radio has a local oscillator which is mixed with the signal from the antenna, and an intermediate frequency of the difference between oscillator and desired signal is filtered from the result and amplified. The oscillator on older receivers would have used a free running tuned circuit, while a newer device might use a phase-locked loop to derive a stable frequency from a crystal.

What [Tom]’s receiver does is take a free-running traditional receiver and use the FPGA as a helper. It has a frequency meter that drives the display, but it also uses the measured figure to adjust the oscillator and keep it on frequency. It has two modes; while tuning it’s a traditional analogue receiver, but when left alone the FPGA stops it drifting. We like it, it’s definitely a special project.

We’ve featured a lot of radio receivers over the years, and this certainly isn’t the only one that’s a bit unconventional.