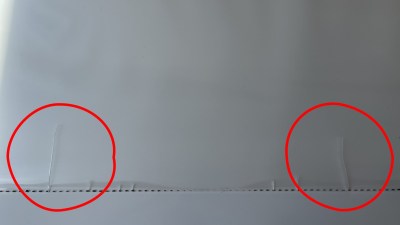

Canadian consumer goods testing site RTINGS has been subjecting 100 TVs to an accelerated TV longevity test, subjecting them so far to over 10,000 hours of on-time, equaling about six years of regular use in a US household. This test has shown a range of interesting issues and defects already, including for the OLED-based TVs. But the most recent issue which they covered is that of uniformity issues with edge-lit TVs. This translates to uneven backlighting including striping and very bright spots, which teardowns revealed to be due to warped reflector sheets, cracked light guides, and burned-out LEDs.

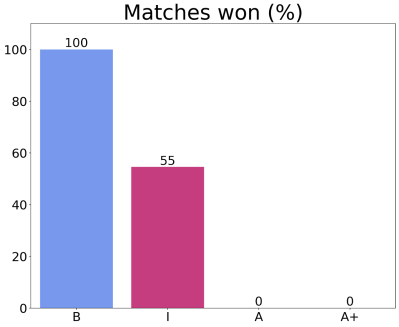

Excluding the 18 OLED TVs, which are now badly burnt in, over a quarter of the remaining TVs in the test suffer from uniformity issues. But things get interesting when contrasting between full-array local dimming (FALD), direct-lit (DL) and edge-lit (EL) LCD TVs. Of the EL types, 7 out of 11 (64%) have uniformity issues, with one having outright failed and others in the process of doing so. Among the FALD and DL types the issue rate here is 14 out of 71 (20%), which is still not ideal after a simulated 6 years of use but far less dramatic.

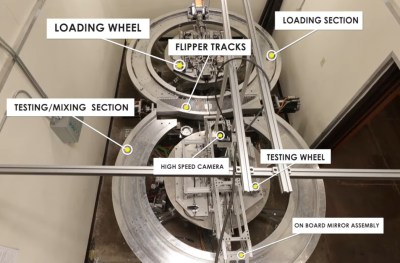

As part of the RTINGS longevity test, failures and issues are investigated and a teardown for analysis, and fixing, is performed when necessary. For these uniformity issues, the EL LCD teardowns revealed burned-out LEDs in the EL LED strips, with cracks in the light-guide plate (LGP) that distributes the light, as well as warped reflector sheets. The LGPs are offset slightly with plastic standoffs to not touch the very hot LEDs, but these standoffs can melt, followed by the LGP touching the hot LEDs. With the damaged LGP, obviously the LCD backlighting will be horribly uneven.

In the LG QNED80 (2022) TV, its edge lighting LEDs were measured with a thermocouple to be running at a searing 123 °C at the maximum brightness setting. As especially HDR (high-dynamic range) content requires high brightness levels, this would thus be a more common scenario in EL TVs than one might think. As for why EL LCDs still exist since they seem to require extreme heatsinking to keep the LEDs from melting straight through the LCD? RTINGS figures it’s because EL allows for LCD TVs to be thinner, allowing them to compete with OLEDs while selling at a premium compared to even FALD LCDs.

Continue reading “Edge-Lit, Thin LCD TVs Are Having Early Heat Death Issues”