Recently [Florin] was in the market for a basic uninterruptible power supply (UPS) to provide some peace of mind for the smart home equipment he had stashed around. Unfortunately, the cheap Serioux LD600LI unit he picked up left a bit to be desired, and required a bit of retrofitting.

To be fair, the issues that [Florin] ended up dealing with were less about the UPS’ capability to deal with these power issues, and more with the USB interface on the UPS. Initially the UPS seemed to communicate happily with HomeAssistant (HA) via Network UPS Tools over a generic USB protocol, after figuring out what device profile matched this re-branded generic UPS. That’s when HA began to constantly lose the connection with the UPS, risking its integration in the smart home setup.

After tearing down the UPS to see what was going on, [Florin] found that it used a fairly generic USB-serial adapter featuring the common Cypress CY7C63310 family of low-speed USB controller. Apparently the firmware on this controller was simply not up to the task or poorly implemented, so a replacement was needed.

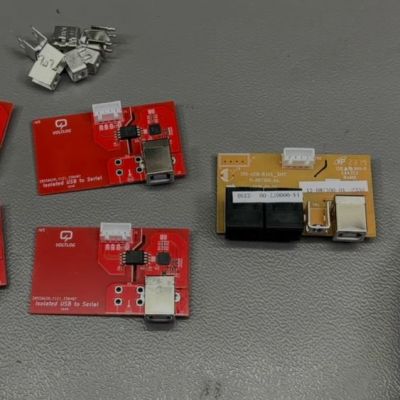

The process and implementation is covered in detail in the video. It’s quite straightforward, taking the 9600 baud serial link from the UPS’ main board and using a Silabs CP2102N USB-to-UART controller to create a virtual serial port on the USB side. These conversion boards have to be fully isolated, of course, which is where the HopeRF CMT8120 dual-channel digital isolator comes into play.

After assembly it almost fully worked, except that a Sonoff Zigbee controller in the smart home setup used the same Silabs controller, with thus the same USB PID/VID combo. Fortunately in Silabs AN721 it’s described how you can use an alternate PID (0xEA63) which fixed this issue until the next device with a CP2102N is installed

As it turns out, the cost of a $40 UPS is actually 10 hours of work and $61 in parts, although one cannot put a value on all the lessons learned here.

Continue reading “The Cost Of A Cheap UPS Is 10 Hours And A Replacement PCB”