Just a few months after releasing the long-awaited second version of his Raspberry Pi Recovery Kit, [Jay Doscher] is back with an alternate take on his latest Pi-in-a-Pelican design. This slightly abridged take on the earlier design should prove to be easier and cheaper to assemble for those playing along at home while keeping the compromises to a minimum.

Probably the biggest change is that the Raspberry Pi 5 has been swapped out for its less expensive and more abundant predecessor. The Pi 4 still packs plenty of punch, but since it requires less power and doesn’t get as hot, it’s less temperamental in a build like this. Gone is the active cooling required by the more powerful single-board computer, and the wiring to distribute power to the Kit’s internal components has been simplified. The high-end military style connectors have been deleted as well. They looked cool, but they certainly weren’t cheap.

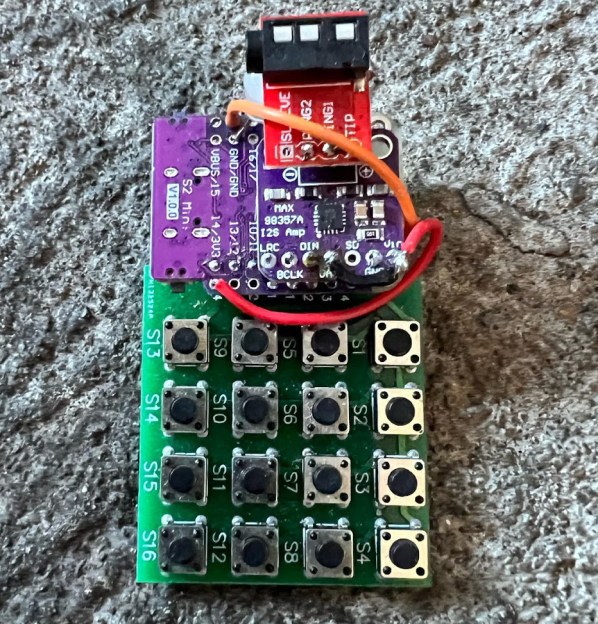

One of the most striking features of the original Recovery Kit was the front-mounted switches — both the networking type that’s intended to help facilitate connecting the Raspberry Pi to whatever hardware is left after the end of the world, and the toggles used to selectively control power to to accessory devices. Both have returned for the Recovery Kit 2B, but they’re also optional, with blank plates available to fill in their vacant spots.

One of the most striking features of the original Recovery Kit was the front-mounted switches — both the networking type that’s intended to help facilitate connecting the Raspberry Pi to whatever hardware is left after the end of the world, and the toggles used to selectively control power to to accessory devices. Both have returned for the Recovery Kit 2B, but they’re also optional, with blank plates available to fill in their vacant spots.

Ultimately, both builds are fairly similar, but there’s enough changes between the two that it will have a notable impact on how much time (and money…) it would take you create one of your own. [Jay] has attempted to offer less intimidating versions of his designs in the past; while other creators take a “one and done” approach to their projects, he seems eager to go back and rethink problems that most others would have considered solved.