3D Printing is great, but it is pretty much the worst way to make any given part– except that every other technique you could use to make that part is too slow and/or expensive, making the 3D print the best option. If only the prints were stiffer, stronger, more durable! [JanTech Engineering] feels your plight and has been hacking away with the M601 command to try embedding different sorts of hardware into his prints for up to 10x greater strength, as seen in the video embedded below.

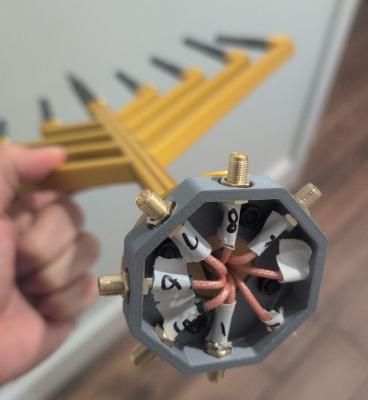

It’s kind of a no-brainer, isn’t it? If the plastic is the weak point, maybe we could reinforce the plastic. Most concrete you see these days has rebar in it, and fiber-reinforced plastic is the only way most people will use resin for structural applications. So, how about FDM? Our printers have that handy M601 “pause print” command built in. By creatively building voids into your parts that you can add stronger materials, you get the best of all possible worlds: the exact 3D printed shape you wanted, plus the stiffness of, say, a pulltruded carbon-fiber rod.

[JanTech] examines several possible inserts, including the aforementioned carbon rods. He takes a second look at urethane foam, which we recently examined, and compares it with less-crushable sand, which might be a good choice when strength-to-weight isn’t an issue. He doesn’t try concrete mix, but we’ve seen that before, too. Various metal shapes are suggested — there are all sorts of brackets and bolts and baubles that can fit into your prints depending on their size — but the carbon rods do come out ahead on strength-to-weight, to nobody’s surprise.

You could do a forged carbon part with a printed mold to get that carbon stiffness, sure, but that’s more work, and you’ve got to handle epoxy resins that some of us have become sensitized to. Carbon rods and tubes are cheap and safer to work with, though be careful cutting them.

Finally, he tries machining custom metal insets with his CNC machine. It’s an interesting technique that’s hugely customizable, but it does require you to have a decent CNC available, and, at that point, you might want to just machine the part. Still, it’s an interesting hybrid technique we haven’t seen before.

Shoving stuff into 3D-printed plastic to make it a better composite object is a great idea and a time-honored tradition. What do you put into your prints? We’d love to know, and so would [Jan]. Leave a comment and let us know.

Continue reading “Pause Print, Add Hardware, And Enjoy Strength”