There’s been a lot of virtual ink spilled about LLMs and their coding ability. Some people swear by the vibes, while others, like the FreeBSD devs have sworn them off completely. What we don’t often think about is the bigger picture: What does AI do to our civilization? That’s the thrust of a recent paper from the Boston University School of Law, “How AI Destroys Institutions”. Yes, Betteridge strikes again.

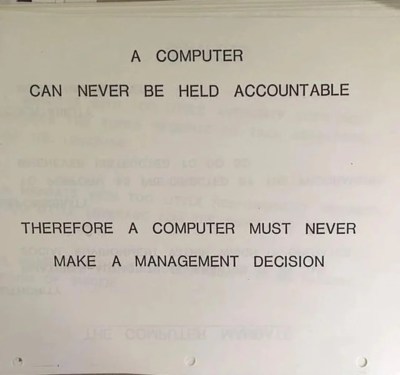

We’ve talked before about LLMs and coding productivity, but [Harzog] and [Sibly] from the school of law take a different approach. They don’t care how well Claude or Gemini can code; they care what having them around is doing to the sinews of civilization. As you can guess from the title, it’s nothing good.

The paper a bit of a slog, but worth reading in full, even if the language is slightly laywer-y. To summarize in brief, the authors try and identify the key things that make our institutions work, and then show one by one how each of these pillars is subtly corroded by use of LLMs. The argument isn’t that your local government clerk using ChatGPT is going to immediately result in anarchy; rather it will facilitate a slow transformation of the democratic structures we in the West take for granted. There’s also a jeremiad about LLMs ruining higher education buried in there, a problem we’ve talked about before.

If you agree with the paper, you may find yourself wishing we could launch the clankers into orbit… and turn off the downlink. If not, you’ll probably let us know in the comments. Please keep the flaming limited to below gas mark 2.