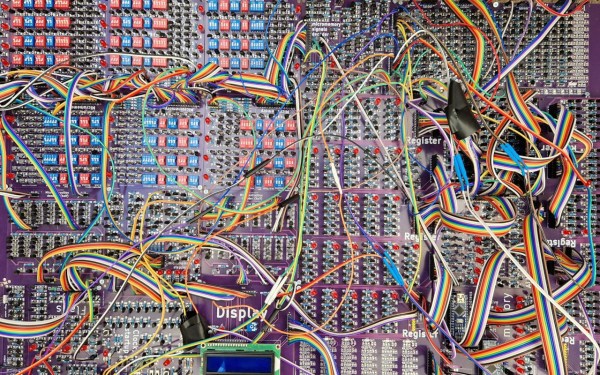

Though mobile devices and Apple Silicon have seen ARM-64 explode across the world, there’s still decent odds you’re reading this on a device with an x86 processor — the direct descendant of the world’s first civilian microprocessor, the Intel 4004. The 4004 wasn’t much good on its own, however, which is why [Klaus Scheffler] and [Lajos Kintli] have produced super-sized discrete chips of the 4001 ROM, 4002 RAM, and 4003 shift register to replicate a 1970s calculator at 10x the size and double the speed, all in time for the 4004’s 50th anniversary.

We featured this project a couple of years back, when it was just a lonely microprocessor. Adding the other MSC-4 series chips enabled the pair to faithfully reproduce the logic of a Busicom 141-PF calculator, the very first to market with Intel’s now-legendary microprocessor. Indeed, this calculator is the raison d’etre for the 4004: Busicom commissioned the whole Micro-Computer System 4-bit (MCS-4) set of chips specifically for this calculator. Only later, once they realized what they had made, did Intel buy the rights back from the Japanese calculator company, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Continue reading “Supersized Calculator Brings The Whole Intel 4004 Gang Together”