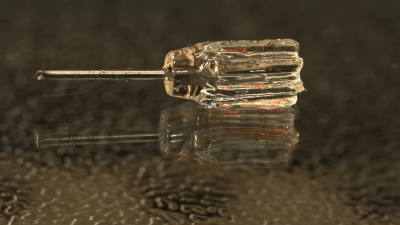

Modern multi-material printers certainly have their advantages, but all that purging has a way to add up to oodles of waste. Tool-changing printers offer a way to do multi-material prints without the purge waste, but at the cost of complexity. Plastic’s cheap, though, so the logic has been that you could never save enough on materials cost to make up for the added capital cost of a tool-changer — that is, until now.

Currently active on Kickstarter, the Snapmaker U1 promises to change that equation. [Albert] got his hands on a pre-production prototype for a review on 247Printing, and what we see looks promising.

The printer features the ubiquitous 235 mm x 235 mm bed size — pretty much the standard for a printer these days, but quite a lot smaller than the bed of what’s arguably the machine’s closest competition, the tool-changing Prusa XL. On the other hand, at under one thousand US dollars, it’s one quarter the price of Prusa’s top of the line offering. Compared to the XL, it’s faster in every operation, from heating the bed and nozzle to actual printing and even head swapping. That said, as you’d expect from Prusa, the XL comes dialed-in for perfect prints in a way that Snapmaker doesn’t manage — particularly for TPU. You’re also limited to four tool heads, compared to the five supported by the Prusa XL.

The U1 is also faster in multi-material than its price-equivalent competitors from Bambu Lab, up to two to three times shorter print times, depending on the print. It’s worth noting that the actual print speed is comparable, but the Snapmaker takes the lead when you factor in all the time wasted purging and changing filaments.

The assisted spool loading on the sides of the machine uses RFID tags to automatically track the colour and material of Snapmaker filament. That feature seems to take a certain inspiration from the Bambu Labs Mini-AMS, but it is an area [Albert] identifies as needing particular attention from Snapmaker. In the beta configuration he got his hands on, it only loads filament about 50% of the time. One can only imagine the final production models will do better than that!

In spite of that, [Albert] says he’s backing the Kickstarter. Given Snapmaker is an established company — we featured an earlier Snapmaker CNC/Printer/Laser combo machine back in 2021— that’s less of a risk than it could be.

Continue reading “A Tool-changing 3D Printer For The Masses”