Photography is great, but sometimes it can get boring just reusing the same wavelengths over and over again. There are other options, though and when [Malcolm Wilson] decided he wanted to explore them, he decided to build a (near) IR camera.

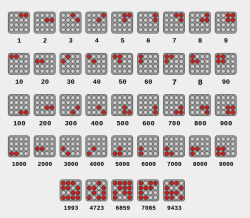

Image : Malcom Wilson.

The housing is an old Yashica Electro 35 — apparently this model was prone to electrical issues, and there are a lot of broken camera bodies floating around– which hides a Pi NoIR Camera v3. That camera module, paired with an IR pass filter, makes for infrared photography like the old Yashica used to do with special film. The camera module is plugged into a Pi Zero 2 W, and it’s powered by a PiSugar battery. There’s a tiny (0.91″) OLED display, but it’s only for status messages. The viewfinder is 100% optical, as the designers of this camera intended. Point, shoot, shoot again.

There’s something pure in that experience; we sometimes find stopping to look at previews pulls one out of the creative zone of actually taking pictures. This camera won’t let you do that, though of course you do get to skip on developing photos. [Malcom] has the Pi set up to connect to his Wifi when he gets home, and he grabs the RAW (he is a photographer, after all) image files via SSH. Follow the link above to [Malcom]’s substack, and you’ll get some design details and his python code.

The Raspberry Pi Foundation’s NoIR camera shows up on these pages from time to time, though rarely so artistically. We’re more likely to see it spying on reptiles, or make magic wands work. So we are quite grateful to [Malcom] for the tip, via Petapixel. Yes, photographers and artists of all stripes are welcome to use the tips line to tell us about their work.

Image: Malcom Wilson