This week, Jonathan Bennett and Rob Campbell talk with Shimon Schocken about Nand2Tetris, the free course about building a computer from first principles. What was the inspiration for the course? Is there a sequel or prequel in the works? Watch to find out!

From Retro To Radiant: 3D Tetris On A LED Matrix

We love seeing retro games evolve into new, unexpected dimensions. Enter [Markus]’ adaptation of 3D Tetris on a custom-built 3x3x12 RGB LED matrix. Developed as a university project, this open-source setup combines coding, soldering, and 3D printing. It’s powered by an ESP32 microcontroller with gameplay controlled by a neat web interface.

This 3D build makes the classic game so much harder to play, that one could argue whether it’s still a game, or has turned into a form of art. Although it is challenging to rotate and drop blocks on such a small scale, for die-hard Tetris fans (and we know you’re out there), there is always someone up to become best at it. Just look at the FastLED-powered light show, the responsive web-based GUI, and fully modular 3D printed housing, this project is a joy to look at even when nobody is playing it. Heck, a game that turned 40 only a year ago should be so mature to entertain itself, shouldn’t it?

From homemade Pong tables to LED cube displays, hobbyists keep finding ways to give classic games a futuristic twist. Projects like this are about pushing boundaries. Hackaday’s archives are full of similar innovations, but why not craft some new ones?

Continue reading “From Retro To Radiant: 3D Tetris On A LED Matrix”

Happy Birthday, Tetris!

Porting DOOM to everything that’s even vaguely Turing complete is a sport for the advanced hacker. But if you are just getting started, or want to focus more on the physical build of your project, a simpler game is probably the way to go. Maybe this explains the eternal popularity of games like PONG, Tetris, Snake, or even Pac-Man. The amount of fun you can have playing the game, relative to the size of the code necessary to implement them, make these games evergreen.

Yesterday was Tetris’ 40th birthday, and in honor of the occasion, I thought I’d bring you a collection of sweet Tetris hacks.

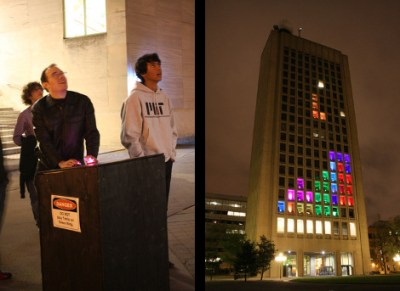

On the big-builds side of things, it’s hard to beat these MIT students who used colored lights in the windows of the Green Building back in 2012. They apparently couldn’t get into some rooms, because they had some dead pixels, but at that scale, who’s complaining? Coming in just smaller, at the size of a whole wall, [Oat Foundry]’s giant split-flap display Tetris is certainly noisy enough.

On the big-builds side of things, it’s hard to beat these MIT students who used colored lights in the windows of the Green Building back in 2012. They apparently couldn’t get into some rooms, because they had some dead pixels, but at that scale, who’s complaining? Coming in just smaller, at the size of a whole wall, [Oat Foundry]’s giant split-flap display Tetris is certainly noisy enough.

Smaller still, although only a little bit less noisy, this flip-dot Tetris is at home on the coffee table, while this one by [Electronoobs] gives you an excuse to play around with RGB LEDs. And if you need a Tetris for your workbench, but you don’t have the space for an extra screen, this oscilloscope version is just the ticket. Or just play it (sideways) on your business card.

All of the above projects have focused on the builds, but if you want to tackle your own, you’ll need to spend some time with the code as well. We’ve got you covered. Way back, former Editor in Chief [Mike Szczys] ported Tetris to the AVR platform. If you need color, this deep dive into the way the NES version of Tetris worked also comes with demo code in Java and Lua. TetrOS is the most minimal version of the game we’ve seen, coming in at a mere 446 bytes, but it’s without any of the frills.

No Tetris birthday roundup would be complete without mentioning the phenomenal “From NAND to Tetris” course, which really does what it says on the package: builds a Tetris game, and your understanding of computing in general, from the ground up.

Can you think of other projects to celebrate Tetris’ 40th? We’d love to see your favorites!

Play Giant Tetris On Second-Floor Window

Sometimes it seems like ideas for projects spring out of nothingness from a serendipitous set of circumstances. [Maarten] found himself in just such a situation, with a combination of his existing Tetris novelty lamp and an awkwardly-sized window on a second-floor apartment, he was gifted with the perfect platform for a giant playable Tetris game built into that window.

To make the giant Tetris game easily playable by people walking by on the street, [Maarten] is building as much of this as possible in the browser. Starting with the controller, he designed a NES-inspired controller in JavaScript that can be used on anything with a touch screen. A simulator display was also built in the browser so he could verify that everything worked without needing the giant display at first. From there it was on to building the actual window-sized Tetris display which is constructed from addressable LEDs arranged in an array that matches the size of the original game.

There were some issues to iron out, as would be expected for a project with this much complexity, but the main thorn in [Maarten]’s side was getting his controller to work in Safari on iPhones. That seems to be mostly settled and there were some other gameplay issues to solve, but the unit is now working in his window and ready to be played by any passers-by, accessed by a conveniently-located QR code. Tetris has been around long enough that there are plenty of unique takes on the game, like this project from 2011 that uses Dance Dance Revolution pads for controllers.

Tetris Goes Round And Round

You’ve probably played some version of Tetris, but [the Center for Creative Learning] has a different take on it. Their latest version features a cylindrical playing field. While it wouldn’t be simple to wire up all those LEDs, it is a little easier, thanks to LED strips. You can find the code for the game on GitHub.

In all, there are 5 LED strips for a display and 13 strips for the playing area, although you can adjust this as long as there are at least 10 rows. The exact number of LEDs will depend on the diameter of the PVC pipe you build it on.

Tetris Goes Full Circle

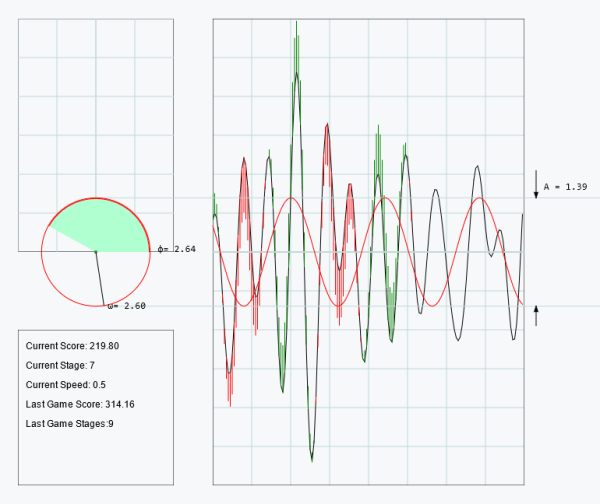

As a game concept, Tetris gave humanity nearly four solid decades of engagement, but with the possibility for only seven possible puzzle pieces it might seem a little bit limiting. Especially now that someone has finally beaten the game, it could be argued that as a society it might be time to look for something new. Sinusoidal Tetris flips these limits on their head with a theoretically infinite set of puzzle pieces for an unmistakable challenge.

Like Tetris, players control a game piece as it slowly falls down the screen. Instead of blocks, however, the game piece is a sinusoid that stretches the entire width of the screen. Players control the phase angle, amplitude, and angular frequency in order to get it to cancel out the randomly-generated wave in the middle of the screen. When the two waves overlap, a quick bit of math is done to add the two waves together. If your Fourier transformation skills aren’t up to the task, the sinusoid will eventually escape the playing field resulting in a game over. The goal then is to continually overlap sinusoids to play indefinitely, much like the original game.

While we’re giving Tetris a bit of a hard time, we appreciate the simplicity of a game that’s managed to have a cultural impact long after the gaming systems it was originally programmed for have become obsolete, and this new version is similar in that regard as well. The game can be quite addictive with a lot to take in at any given moment. If you’re more interested in the programming for these types of games than the gameplay, though, take a look at this deep-dive into Tetris for the NES.

Tetris On An Oscilloscope, The Software Way

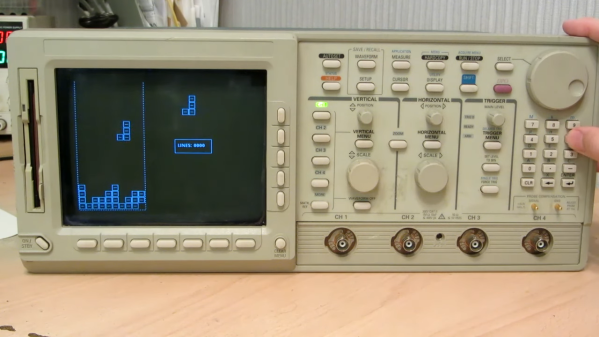

When we talk about video games on an oscilloscope, you’d be pardoned for assuming the project involved an analog CRT scope in X-Y mode, with vector graphics for something like Asteroids or BattleZone. Alas, this oscilloscope Tetris (Russian language, English translation) isn’t that at all — but that doesn’t make it any less cool.

If you’re interested in recreating [iliasam]’s build, it’ll probably help to be a retro-oscilloscope collector. The target instrument here is a Tektronix TDS5400, a scope from that awkward time when everything was going digital, but CRTs were still cheaper and better than LCDs. It’s based on a Motorola 68EC040 processor, sports a boatload of discrete ICs on its main PCB, and runs VxWorks for its OS. Tek also provided a 3.5″ floppy drive on this model, to save traces and the like, as well as a debug port, which required [iliasam] to build a custom UART adapter.

All these tools ended up being the keys to the kingdom, but getting the scope to run arbitrary code was still a long and arduous process, with a lot of trial and error. It’s a good story, but the gist is that after dumping the firmware onto the floppy and disassembling it in Ghidra, [iliasam] was able to identify the functions used to draw graphics primitives on the CRT, as well as the functions to read inputs from the control panel. The result is the simple version of Tetris seen in the video below. If you’ve got a similar oscilloscope, the code is up on GitHub.

Care for a more hardware-based game-o-scope? How about a nice game of Pong? Or perhaps a polar breakout-style game is what you’re looking for. Continue reading “Tetris On An Oscilloscope, The Software Way”