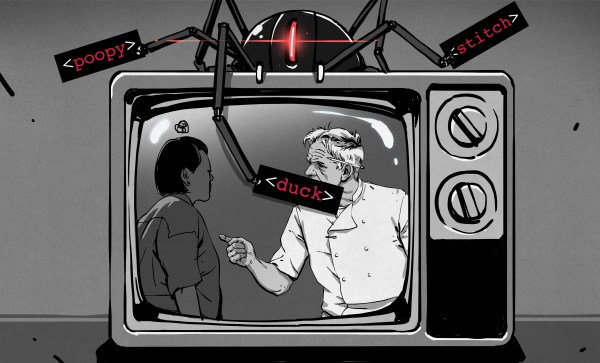

The recent flurry of videos and posts about the TVGuardian foul language filter brought back some fond memories. I was the chief engineer on this project for most of its lifespan. You’ve watched the teardowns, you’ve seen the reverse engineering, now here’s the inside scoop.

Gumby is Born

Back in 1999, my company took on a redesign project for the TVG product, a box that replaced curse words in closed-captioning with sanitized equivalents. Our first task was to take an existing design that had been produced in limited volumes and improve it to be more easily manufactured.

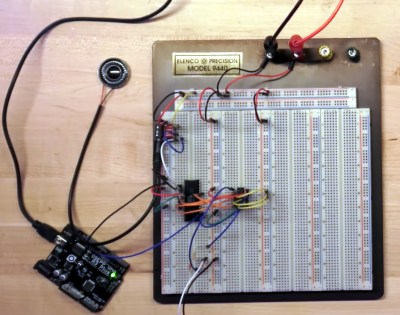

The original PCB used all thru-hole components and didn’t scale well to large quantity production. Replacing the parts with their surface mount equivalents resulted in Model 101, internally named Gumby for reasons long lost. If you have a sharp eye, you will have noticed something odd about two parts on the board as shown in [Ben Eater]’s video. The Microchip PIC and the Zilog OSD chip had two overlapping footprints, one for thru-hole and one for SMD. Even though we preferred SMD parts, sometimes there were supply issues. This was a technique we used on several designs in our company to hedge our bets. It also allowed us to use a socketed ICs for testing and development. Continue reading “The Story Behind The TVGuardian Curse Catcher”