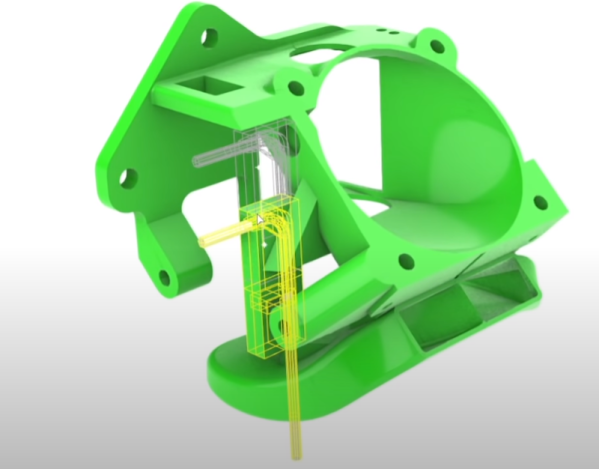

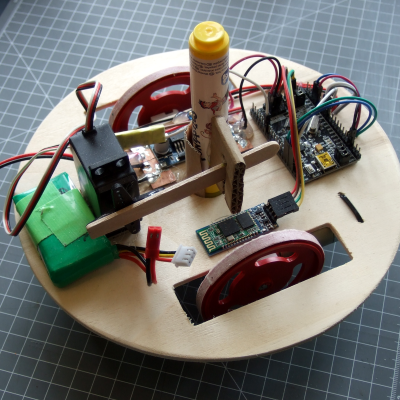

My son was into “Secret Coders“, a graphic novel series wherein a pair of kids discover and thwart a plot to take over the world by learning to program in the LOGO computer language. When I told him that these “turtle bots” were originally actually real physical things, he wanted one. So we built one out of some nice geared DC motors I had lying around.

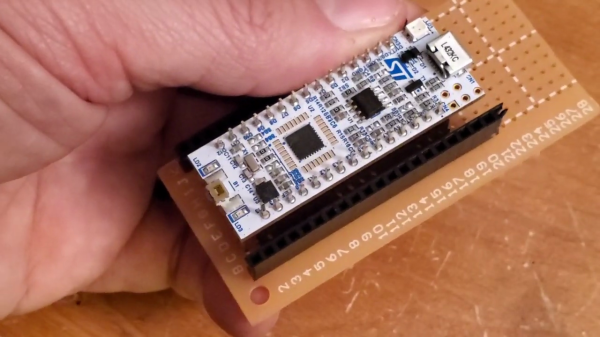

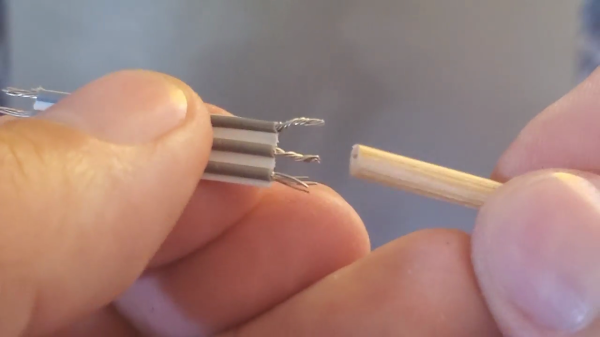

A turtle bot has essentially three jobs: move forward in a straight line a controlled distance, turn a given number of degrees, and raise and lower a pen. If you’re already screaming “use stepper motors!” at your screen, well, you’re probably right. But I had these nice Faulhaber/Micromo geared motors with encoders that were just collecting dust in the closet, so I used ’em. And because of that, the robot stumbles on two of its three goals in life — the servo pen lifter works just fine.

Perfectly matched DC motors don’t exist. Of course I knew this, because I’ve built bots with DC motors before. But they’ve all had complex control mechanisms and/or feedback that made it moot. Not here. This bot needs to drive perfectly straight without any lines to guide it or more interesting navigation algorithms.

Perfectly matched DC motors don’t exist. Of course I knew this, because I’ve built bots with DC motors before. But they’ve all had complex control mechanisms and/or feedback that made it moot. Not here. This bot needs to drive perfectly straight without any lines to guide it or more interesting navigation algorithms.

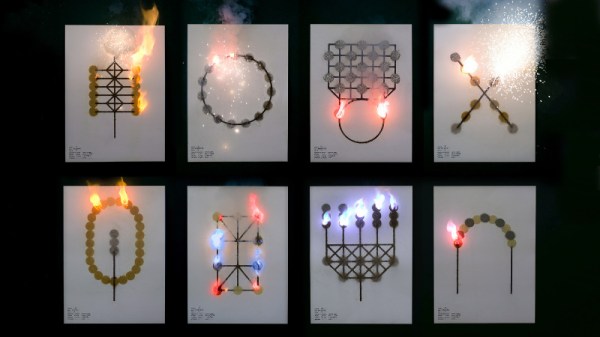

We spent a good half hour driving it around in not-quite-but-almost squares, tweaking each side’s PWMs, running the motors backwards for short bursts to brake the wheels, and generally trying to map degrees of rotation to milliseconds of motor drive. And you know what, my son enjoyed it. The concepts were simple enough for a second grader, and guessing the right PWM values was like a game. When we finally got it good enough, there was a small celebration.

Of course I know that what it really needs is encoder feedback. I installed those encoder gearmotors on purpose after all. But dealing with quadrature and probably a PID loop to control and sync the two sides is not for my son, at least not for another couple years. (They do learn closed-loop control theory in fourth grade these days, right?) I’ll have to do that all offline some night while he’s sleeping.

But I hope he’ll remember the lessons learned from stabbing at it the naive way. Abstractions are great, but no two motors are ever perfectly alike. You’d think you could just calibrate it out, but the motors differ in driven and coasting behavior, so you’ve got a lot more calibrating to do than you think at first. The real world is tough, and although it’s important to have theory and ideas and abstractions to guide you, you’re going to have to tweak to make it work when the wheels hit the floor. But also that it’s fun to do so, and super rewarding when it finally draws a wonky square.