For someone programming in a high-level language like Python, or even for people who interact primarily with their operating system and the software running on it, it can seem like the computer hardware is largely divorced from the work. Yes, the computer has to be physically present to do something like write a Hackaday article, but most of us will not understand the Assembly language, machine code, or transistor layout well enough to build up to what makes a browser run. [Francis Stokes] is a different breed, though, continually probing these mysterious low-level regions of our computerized world where he was recently able to send an Ethernet packet from scratch.

Ferrites Versus Ethernet In The Ham Shack

For as useful as computers are in the modern ham shack, they also tend to be a strong source of unwanted radio frequency interference. Common wisdom says applying a few ferrite beads to things like Ethernet cables will help, but does that really work?

It surely appears to, for the most part at least, according to experiments done by [Ham Radio DX]. With a particular interest in lowering the noise floor for operations in the 2-meter band, his test setup consisted of a NanoVNA and a simple chunk of wire standing in for the twisted-pair conductors inside an Ethernet cable. The NanoVNA was set to sweep across the entire HF band and up into the VHF; various styles of ferrite were then added to the conductor and the frequency response observed. Simply clamping a single ferrite on the wire helped a little, with marginal improvement seen by adding one or two more ferrites. A much more dramatic improvement was seen by looping the conductor back through the ferrite for an additional turn, with diminishing returns at higher frequencies as more turns were added. The best performance seemed to come from two ferrites with two turns each, which gave 17 dB of suppression across the tested bandwidth.

The question then becomes: How do the ferrites affect Ethernet performance? [Ham Radio DX] tested that too, and it looks like good news there. Using a 30-meter-long Cat 5 cable and testing file transfer speed with iPerf, he found no measurable effect on throughput no matter what ferrites he added to the cable. In fact, some ferrites actually seemed to boost the file transfer speed slightly.

Ferrite beads for RFI suppression are nothing new, of course, but it’s nice to see a real-world test that tells you both how and where to apply them. The fact that you won’t be borking your connection is nice to know, too. Then again, maybe it’s not your Ethernet that’s causing the problem, in which case maybe you’ll need a little help from a thunderstorm to track down the issue. Continue reading “Ferrites Versus Ethernet In The Ham Shack”

Ethernet History: Why Do We Have Different Frame Types?

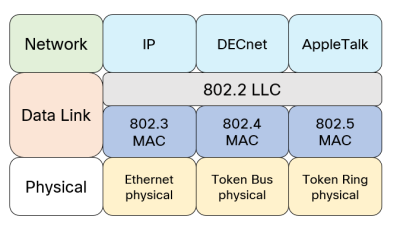

Although Ethernet is generally considered to be a settled matter, its history was anything but peaceful, with its standardization process (under Project 802) leaving its traces to this very day. This is very clear when looking at the different Ethernet frame types in use today, and with many more historical types. While Ethernet II is the most common frame type, 802.2 LLC (Logical Link Control) and 802 SNAP (Subnetwork Access Protocol) are the two major remnants of this struggle that raged throughout the 1980s, even before IEEE Project 802 was created. An in-depth look at this history with all the gory details is covered in this article by [Daniel].

We covered the history of Ethernet’s original development by [Robert Metcalfe] and [David Boggs] while they worked at Xerox, leading to its commercial introduction in 1980, and eventual IEEE standardization as 802.3. As [Daniel]’s article makes clear, much of the problem was that it wasn’t just about Ethernet, but also about competing networking technologies, including Token Ring and a host of other technologies, each with its own gaggle of supporting companies backing them.

Over time this condensed into three subcommittees:

- 802.3: CSMA/CD (Ethernet).

- 802.4: Token bus.

- 802.5: Token ring.

An abstraction layer (the LLC, or 802.2) would smooth over the differences for the protocols trying to use the active MAC. Obviously, the group behind the Ethernet and Ethernet II framing push (DIX) wasn’t enamored with this and pushed through Ethernet II framing via alternate means, but with LLC surviving as well, yet its technical limitations caused LLC to mutate into SNAP. These days network engineers and administrators can still enjoy the fallout of this process, but it was far from the only threat to Ethernet.

Ethernet’s transition from a bus to a star topology was enabled by the LANBridge 100 as an early Ethernet switch, allowing it to scale beyond the limits of a shared medium. Advances in copper wiring (and fiber) have further enabled Ethernet to scale from thin- and thicknet coax to today’s range of network cable categories, taking Ethernet truly beyond the limits of token passing, CSMA/CD and kin, even if their legacy will probably always remain with us.

A Really Low Level Guide To Doing Ethernet On An FPGA

With so much of our day-to-day networking done wirelessly these days, it can be easy to forget about Ethernet. But it’s a useful standard and can be a great way to add a reliable high-throughput network link to your projects. To that end, [Robert Feranec] and [Stacy Rieck] whipped up a tutorial on how to work with Ethernet on FPGAs.

As [Robert] explains, “many people would like to transfer data from FPGA boards to somewhere else.” That basically sums up why you might be interested in doing this. The duo spend over an hour stepping through doing Ethernet at a very low level, without using pre-existing IP blocks to make it easier. The video explains the basic architecture right down to the physical pins on the device and what they do, all the way up to the logic blocks inside the device that do all the protocol work.

If you just want to get data off an embedded project, you can always pull in some existing libraries to do the job. But if you want to really understand Ethernet, this is a great place to start. There’s no better way to learn than doing it yourself. Files are on GitHub for the curious. Continue reading “A Really Low Level Guide To Doing Ethernet On An FPGA”

How DEC’s LANBridge 100 Gave Ethernet A Fighting Chance

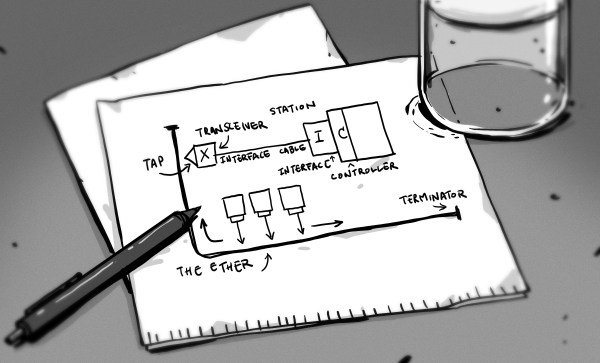

When Ethernet was originally envisioned, it would use a common, shared medium (the ‘Ether’ part), with transmitting and collision resolution handled by the carrier sense multiple access with collision detection (CSMA/CD) method. While effective and cheap, this limited Ethernet to a 1.5 km cable run and 10 Mb/s transfer rate. As [Alan Kirby] worked at Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC) in the 1980s and 1990s, he saw how competing network technologies including Fiber Distributed Data Interface (FDDI) – that DEC also worked on – threatened to extinguish Ethernet despite these alternatives being more expensive. The solution here would be store-and-forward switching, [Alan] figured.

After teaming up with Mark Kempf, both engineers managed to convince DEC management to give them a chance to develop such a switch for Ethernet, which turned into the LANBridge 100. As a so-called ‘learning bridge’, it operated on Layer 2 of the network stack, learning the MAC addresses of the connected systems and forwarding only those packets that were relevant for the other network. This instantly prevented collisions between thus connected networks, allowed for long (fiber) runs between bridges and would be the beginning of the transformation of Ethernet as a shared medium (like WiFi today) into a star topology network, with each connected system getting its very own Ethernet cable to a dedicated switch port.

SatCat5: UART, SPI And I2C Via Ethernet With FPGA-Based Design

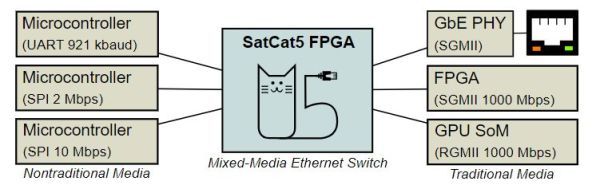

To the average microcontroller, Ethernet networks are quite a step up from the basic I2C, SPI and UART interfaces, requiring either a built-in Ethernet MAC or SPI-based MAC, with tedious translation between Ethernet and those other interfaces. Yet what if this translation could be done automatically and transparently? This is what the SatCat5 FPGA-based project by [The Aerospace Corporation] aims to provide: a gateway akin to an unmanaged Ethernet switch that also supports those non-Ethernet links. Recently they answered a range of questions about the project on Hacker News.

The project name comes from the primary target audience: smallsat and cubesat developers, which is an area where being able to route more traffic over a common Ethernet-based bus is a major boon. The provided Xilinx Artix-7-based reference design (pictured) gives a good idea of how it can be used: it combines an Arty A7 development board with a custom PCB containing an Ethernet switch IC (SJA1105), TJA1100 transceiver, two RJ45 jacks and four PMOD connectors, here connected to two UARTs for bidirectional communication between them. Ethernet frame encapsulation is provided using the standard Serial Line Internet Protocol (SLIP), with more details covered in the FAQ. At a minimum an FPGA like a Lattice iCE40 is required, with an MCU capable of using the provided C++ libraries, or a custom implementation.

Thanks to [STR-Alorman] for the tip.

Ethernet For Hackers: Transformers, MACs And PHYs

We’ve talked about Ethernet basics, and we’ve talked about equipment you will find with Ethernet. However, that’s obviously not all – you also need to know how to add Ethernet to your board and to your microcontroller. Such low-level details are harder to learn casually than the things we talked about previously, but today, we’re going to pick up the slack.

You might also have some very fair questions. What are the black blocks near Ethernet sockets that you generally will see on boards, and why do they look like nothing else you see on circuit boards ever? Why do some boards, like the Raspberry Pi, lack them altogether? What kind of chip do you need if you want to add Ethernet support to a microcontroller, and what might you need if your microcontroller claims to support Ethernet? Let’s talk.

Transformers Make The Data World Turn

One of the Ethernet’s many features is that it’s resilient, and easy to throw around. It’s also galvanically isolated, which means you don’t need a ground connection for a link either – not until you want a shield due to imposed interference, at which point, it might be that you’re pulling cable inside industrial machinery. There are a few tricks to Ethernet, and one such fundamental Ethernet trick is transformers, known as “magnetics” in Ethernet context.

Each pair has to be put through a transformer for the Ethernet port to work properly, as a rule. That’s the black epoxy-covered block you will inevitably see near an Ethernet port in your device. There are two places on the board as far as Ethernet goes – before the transformer, and after the transformer, and they’re treated differently. After the transformer, Ethernet is significantly more resilient to things like ground potential differences, which is how you can wire up two random computers with Ethernet and not even think about things like common mode bias or ground loops, things we must account for in audio, or digital interfaces that haven’t yet gone optical somehow.

Continue reading “Ethernet For Hackers: Transformers, MACs And PHYs”