More and more, the power grid is distributed. Houses have solar panels on their roofs, and where possible, that excess power is sold back to the grid. The current trend is towards smart meters that record consumption for an entire household and relay it back to the power plant every day or so. The future is decentralized, through, and a meter that is smart once a day simply won’t do. A team on Hackaday.io has put together the ultimate in decentralized energy modernization. It’s the InternetS of Energy, and it removes the need for power companies completely.

The team has identified a few key features of the current power grid that don’t make sense in the age of the Internet. The power company doesn’t have extremely granular data, and sending power over long distances is either inefficient or expensive. The solution for this is to have distributed power plants, all connected together into a truly intelligent power grid.

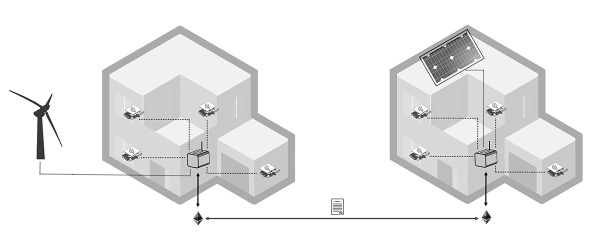

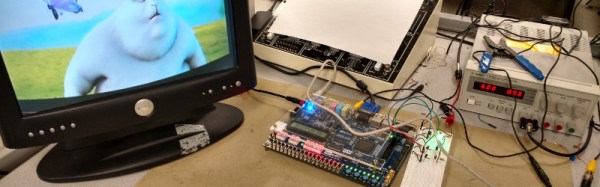

This InternetS of Energy uses open-source energy monitoring systems running the Ethereum client to push power-usage data onto the blockchain. This makes the grid secure and pseudonymous, and if the banking industry is any indication, something like this is the future of economic transactions.

While it may not be the best solution for mature power grids, it is an extremely interesting avenue of research for developing nations. Wherever local resources allow it, electricity can be generated and sent to where it’s needed. It’s exactly what the power grid would be if it were re-designed today from scratch, and an excellent candidate for the 2016 Hackaday Prize.