We’ve probably all taken a look at the rash of cheap Intel-Atom-based tablet computers and wondered whether therein lies an inexpensive route to a portable PC. Such limited hardware laden down with a full-fat Windows installation fails to shine, but maybe if we could get a higher-performance OS on there it could be a useful piece of kit.

[donothingloop] has an Intel tablet, a TrekStore Wintron 7, bought for the princely sum of $60. Windows 10 didn’t excite him, so he decided to put Ubuntu on it, or more specifically to put Ubuntu on an SD card to try it on the Wintron before overwriting the Windows installation. His problem with that was a bug in the Baytrail Atom chipset which limits the speed of SD card access and made Ubuntu very slow, and in trying to fix the speed issue he managed to disable a setting in the BIOS which had the effect of bricking the machine. A show-stopper when the BIOS is in a tiny SPI Flash chip and can’t be wiped or restored.

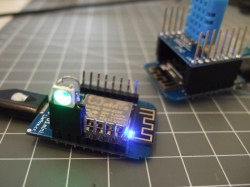

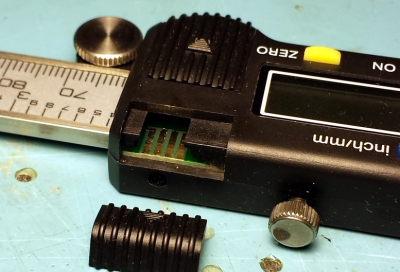

What followed was an epic of desoldering the BIOS chip and reflashing it, though that description makes the process sound deceptively easy. The specification says it is a 1.8V device, so after attempts to flash it using an ESP8266 and then a home-made level-shifter failed, he was stumped. With nothing but a cheap tablet to lose, he tried the chip in a 3.3V programmer, and to his amazement despite the significant overvoltage, it survived. Resoldering the chip to the motherboard presented him with a working tablet that would live to fight another day.

We’d have said that this work might reside in the “Don’t try this at home” category, but since Hackaday readers are exactly the kind of people who do try this kind of thing at home it’s interesting and reassuring to see that it can be done, and to see how someone else did it. A tablet that can be bricked through a mere BIOS setting though is something a manufacturer should be ashamed of.

We like unbricking stories here at Hackaday, something about winning against the odds appeals to us. In the past we’ve covered Blu-ray drives crippled by dodgy DRM and routers rescued with a Raspberry Pi, but the crown has to be taken by the phone rescued with a resistor made using paperclips and pencil lead.

For hardware, we’re using a WeMos D1 Mini because they’re really cute, and absolutely dirt cheap, but basically any ESP module will do. For instance, you can do the same on the simplest ESP-01 module if you’ve got your own USB-serial adapter and are willing to jumper some pins to get it into bootloader mode. If you insist on a deluxe development board that bears the Jolly Wrencher, we know some people.

For hardware, we’re using a WeMos D1 Mini because they’re really cute, and absolutely dirt cheap, but basically any ESP module will do. For instance, you can do the same on the simplest ESP-01 module if you’ve got your own USB-serial adapter and are willing to jumper some pins to get it into bootloader mode. If you insist on a deluxe development board that bears the Jolly Wrencher, we know some people.

a simple interface circuit for translating the logic levels, and an interrupt-driven

a simple interface circuit for translating the logic levels, and an interrupt-driven