[Mr. Volt] mentions that some of the commenters on his videos believed that he shouldn’t be making large, retro computer themed communicator watches. He believes they are wrong, naturally we are compelled to agree with him.

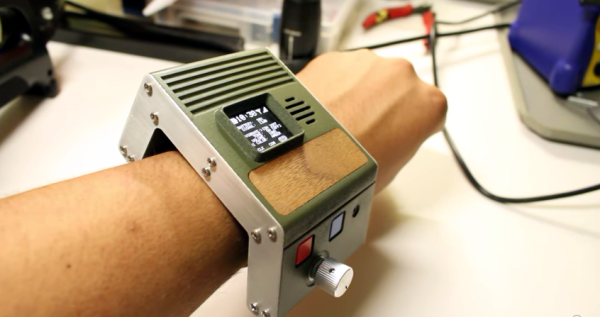

In his latest build he has produced a rather well-built and large cell-phone watch. After the untimely death of an Apple II cellphone watch, he decided to up his game and make one that could take more of a beating. The case is 3D printed, which is hard to believe given the good finish. He must have spent a long time sanding the prints. Some wood veneer for looks and aluminum panels for strength complete the assembly.

In his latest build he has produced a rather well-built and large cell-phone watch. After the untimely death of an Apple II cellphone watch, he decided to up his game and make one that could take more of a beating. The case is 3D printed, which is hard to believe given the good finish. He must have spent a long time sanding the prints. Some wood veneer for looks and aluminum panels for strength complete the assembly.

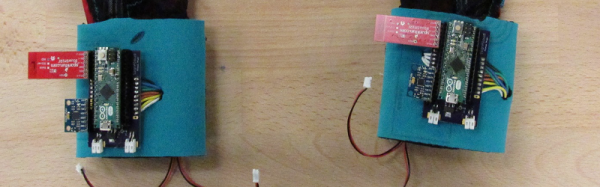

The electronics are a Teensy and a GSM module. It looks like he places calls by calling the operator since the wrist communicator only has four inputs: a red button, a blue button, and a momentary switch rotary encoder.

The communicator appears to work really smoothly, and it would certainly draw attention to him were he to wear it anywhere other than the Wasteland. Video after the break.

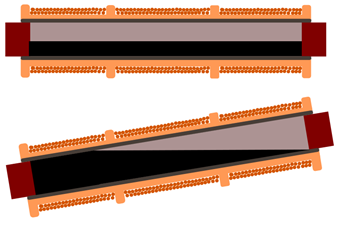

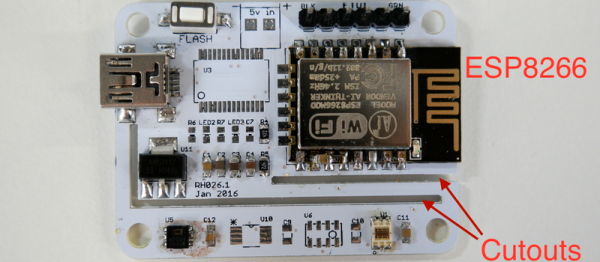

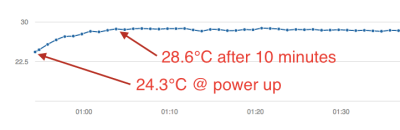

Next came the clever bit. [Richard] put cutouts into the board to hopefully stop the flow of heat from the ESP8266 module to the temperature sensor. Again, he found that the board heats up by around four degrees Celcius or nine degrees Farenheit. That’s a horrible result in any units.

Next came the clever bit. [Richard] put cutouts into the board to hopefully stop the flow of heat from the ESP8266 module to the temperature sensor. Again, he found that the board heats up by around four degrees Celcius or nine degrees Farenheit. That’s a horrible result in any units. Fail of the Week is a Hackaday column which celebrates failure as a learning tool. Help keep the fun rolling by writing about your own failures and

Fail of the Week is a Hackaday column which celebrates failure as a learning tool. Help keep the fun rolling by writing about your own failures and