Walking, jumping, rolling, flying, swimming – robotic locomotion is limited only by the imagination of the inventor. [Roger Rabbit] apparently has a pretty vivid imagination, because he’s building robots that move like worms.

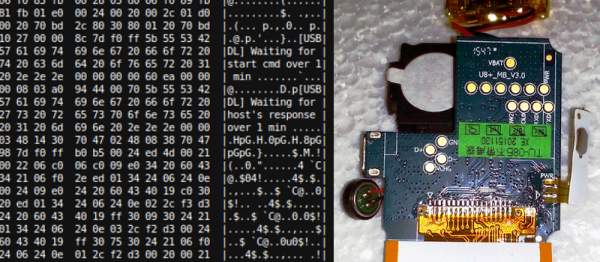

Version 1 of [Roger]’s robot is only semi-vermiform and is more of tube climber. It has a pair of 3D-printed pantographs that expand and contract with servos and move along the robot’s axis on a stepper-driven lead screw. An Arduino reads sensors and coordinates the expansion of the pantographs to grip the internal diameter of a pipe and push the worm-bot along. It’s a slow but effective way to get around in the limited confines of a pipe.

Version 1 of [Roger]’s robot is only semi-vermiform and is more of tube climber. It has a pair of 3D-printed pantographs that expand and contract with servos and move along the robot’s axis on a stepper-driven lead screw. An Arduino reads sensors and coordinates the expansion of the pantographs to grip the internal diameter of a pipe and push the worm-bot along. It’s a slow but effective way to get around in the limited confines of a pipe.

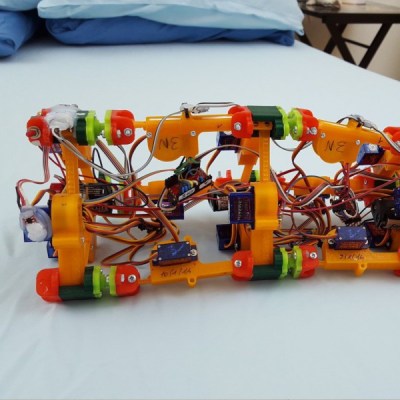

The next iteration, dubbed [Wolly], is much more worm-like and not restricted to pipe-running. It has four expandable triangular frames connected to each other with rack-and-pinion backbones. The first frame contracts, the racks push it forward, it expands, the next contracts, and soon it’s doing the worm across the floor. Still slow, but pretty neat to watch, and you can see how it can be steered. It might even be able to roll around its long axis, and it’d make a decent tube climber as well.

This creepy autonomous worm-bot seems very similar to [Wolly], but aside from that we haven’t covered too many robots like these. There’s a lot of thought and effort in these worm-bots, and we’re keen to see where [Roger] takes this unique robot body plan.