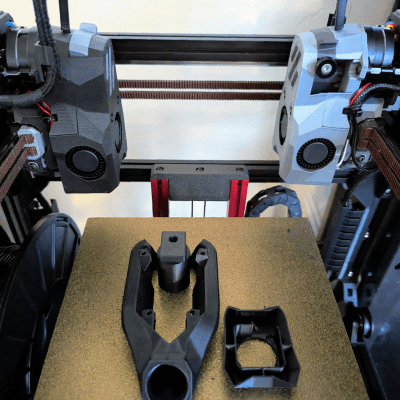

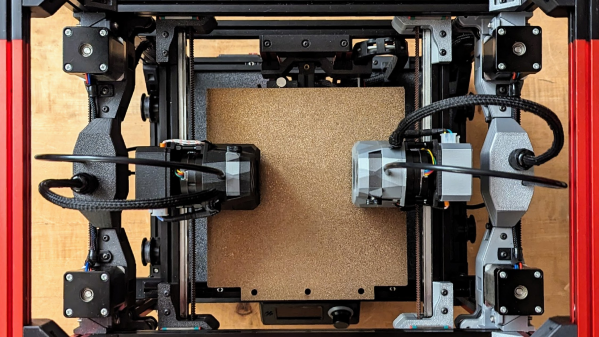

What’s a dual gantry 3D printer? It’s a machine with two completely independent XY motion systems, with two independent hot ends, sharing the same build platform. That might be a little hard to visualize, so head over to [Zruncho 3D]’s Dueling Zero project and get a good look at what what a dual gantry machine looks like.

Let’s take a moment to quickly cover the different ways to create multi-filament prints before we dive into what’s different with Dueling Zero. One way to print in multiple filaments (for example, multiple colors) is to swap filaments between a single print head, which is what the Prusa MMU and the Bambu AMS do. However, the main tradeoff is that the filament swapping process can be time-consuming. Another option is IDEX (Independent Dual EXtruder) which has two separate hot ends on the same axis. The main downside there is that an IDEX printer has essentially doubled the moving mass on the axis, which limits speed and can affect print quality. Then there’s toolchanging printers like the Prusa XL, which swap entire heads as needed but have a much higher cost.

The Dueling Zero instead adds a completely independent second gantry, so it has two print heads (like an IDEX) but thanks to the mechanical design it acts much more like a single-extruder 3D printer in terms of print quality and motion control. Speed and acceleration aren’t limited by added mass, either, which is good because slow printers are rapidly falling out of style.

We love how clean and finished the design is. At its core, [Zruncho 3D]’s dual gantry mod (designated D0) is based on the Voron Zero design. Dueling Zero is, to our knowledge, the only open-source and fully documented dual gantry printer out there, which is pretty wild. Watch it in action in the short video, embedded below.

Continue reading “Tool Changing? Bah! Just Add A Second Gantry”

![The hot end of the EasyThreed K9 is actually pretty nifty. (Credit: [Thomas Sanladerer])](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/cheapest_fdm_printer_hotend.jpg?w=250)