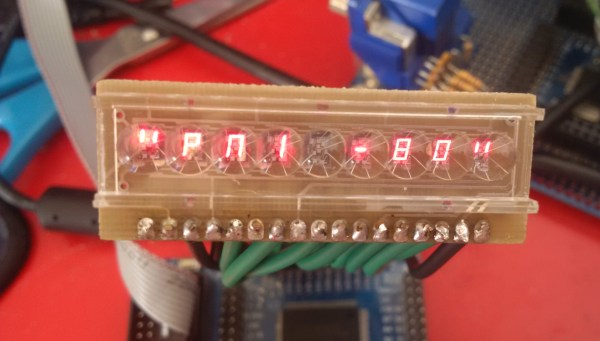

This year’s Hackaday Prize included a category for the Best Product, and there is perhaps no project that has inspired more people to throw money at their computer screens than [Oscar Vermeulen]’s PiDP-8/I. It’s a replica of the PDP-8/I from 1968. Instead of discrete electronics driving the blinkenlights and switches on the front of this computer, [Oscar]’s version uses a Raspberry Pi and the incredible SIMH emulator for dozens of old mainframes and minicomputers. It is, for all intents and purposes, a miniaturized version of a 50 year old computer that will fit on your desk and is powered by a phone charger.

Check out the video of [Oscar]’s talk below then join us after the break for more discussion of his work.

Continue reading “Experiences In Developing An Electronics Kit”

But what, you might ask, makes the 3458A such a significant and desirable instrument? It’s all in the digits. The 3458A is one of the few 8.5 digit multimeters available. It is therefore sensitive to microvolt deflections on 10 volt measurements. It is this ability to distinguished tiny changes on large signals that sets high precision multimeters apart. Imagine weighing an elephant and being able to count the number of flies that land on its back by the change in weight. The 3458A accomplishes a similar feat.

But what, you might ask, makes the 3458A such a significant and desirable instrument? It’s all in the digits. The 3458A is one of the few 8.5 digit multimeters available. It is therefore sensitive to microvolt deflections on 10 volt measurements. It is this ability to distinguished tiny changes on large signals that sets high precision multimeters apart. Imagine weighing an elephant and being able to count the number of flies that land on its back by the change in weight. The 3458A accomplishes a similar feat.