There are a few dozen classic re-imaginings of classic game consoles, using hardware ranging from the ATMegas of the Uzebox to everyone’s favorite, stuffing some ROMs on a Raspi and calling it a day. You don’t necessarily learn anything doing that, which puts [Mike]’s custom game console head and shoulders above the rest.

The build started off as a plan for a Z80 computer with a dual ATMega GPU. He progressed far enough in the design where it would have been a masterpiece, but the inability to mill double-sided boards at home killed the design. Plans then moved on to an FPGA, then to an ATMega with the Analog Device AD725 PAL/NTSC encoder chip. That idea had a similar architecture to the Uzebox, but [Mike] wanted more power. He eventually settled on a PIC32 with the AD725.

This setup was capable of pumping out some impressive graphics, but for moving bits to a screen, you need DMA. [Mike] ran into a problem where the DMA timer runs at a maximum rate of 3.7 MHz. It’s a problem documented in a few projects, leading [Mike] to change his plan once again, this time to the STM32F4.

The bugs are worked out, and now [Mike] can stream a whole lot of pixels to a screen while still having some processing power left over to play a game. It’s a project that’s more than a year and a half old at this point, and so far he’s learned a lot.

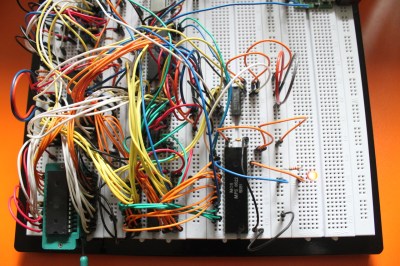

[Dirk] has some great documentation to go with his computer. He started with a classic MOS 6502 processor. He surrounded the processor with a number of support chips correct for the early 80’s period. RAM is easy-to -use static RAM, while ROM is handled by UV erasable EPROM. A pair of MOS 6522 Versatile Interface Adapter (VIA) chips connect the keyboard, LCD, and any other peripherals to the CPU. Sound is of course provided by the 6581 SID chip. All this made for a heck of a lot of wires when built up on a breadboard. The only thing missing from this build is a way to store software written on the machine. [Dirk] already is looking into ways to add an SD card interface to the machine.

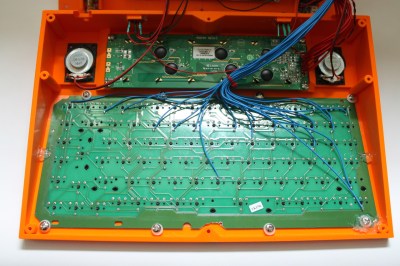

[Dirk] has some great documentation to go with his computer. He started with a classic MOS 6502 processor. He surrounded the processor with a number of support chips correct for the early 80’s period. RAM is easy-to -use static RAM, while ROM is handled by UV erasable EPROM. A pair of MOS 6522 Versatile Interface Adapter (VIA) chips connect the keyboard, LCD, and any other peripherals to the CPU. Sound is of course provided by the 6581 SID chip. All this made for a heck of a lot of wires when built up on a breadboard. The only thing missing from this build is a way to store software written on the machine. [Dirk] already is looking into ways to add an SD card interface to the machine. The home building didn’t stop there though. [Dirk] designed and etched his own printed circuit board (PCB) for his computer. DIY PCBs with surface mount components are easy these days, but things are a heck of a lot harder with older through hole components. Every through hole pin and via had to be drilled, and soldered to the top and bottom layers of the board. Not to mention the fact that both layers had to line up perfectly to avoid missing holes! To say this was a lot of work would be an understatement.

The home building didn’t stop there though. [Dirk] designed and etched his own printed circuit board (PCB) for his computer. DIY PCBs with surface mount components are easy these days, but things are a heck of a lot harder with older through hole components. Every through hole pin and via had to be drilled, and soldered to the top and bottom layers of the board. Not to mention the fact that both layers had to line up perfectly to avoid missing holes! To say this was a lot of work would be an understatement. [Dirk] designed a custom 3D printed case for his computer and printed it out on his Ultimaker. To make things fit, he created his design in halves, and glued the case once printing was complete.

[Dirk] designed a custom 3D printed case for his computer and printed it out on his Ultimaker. To make things fit, he created his design in halves, and glued the case once printing was complete.