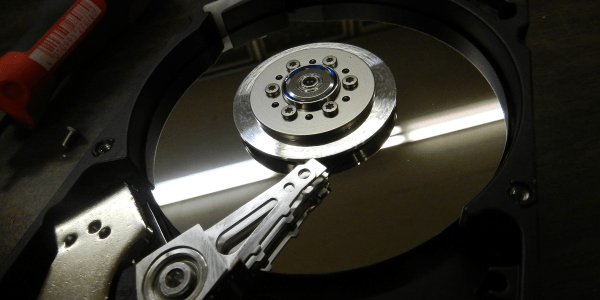

It should have been another fine day, but not all was well in paradise. Few things bring a creeping feeling of doom like a computer that hardlocks and then refuses to boot. The clicking sound coming from the tower probably isn’t a good sign either. Those backups are up to date, right? Right?

There are some legends and old stories about hard drive repair. One of my favorites is the official solution to stiction for old drives: Smack it with a mallet. Another trick I’ve heard repeatedly is to freeze a hard drive before trying to read data off of it. This could actually be useful in a couple instances. The temperature change can help with stiction, and freezing the drive could potentially help an overheating drive last a bit longer. The downside is the potential for condensation inside the drive. Don’t turn to one of these questionable fixes unless you’ve exhausted the safer options.

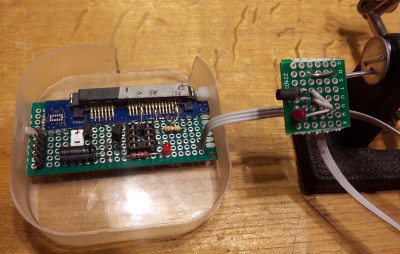

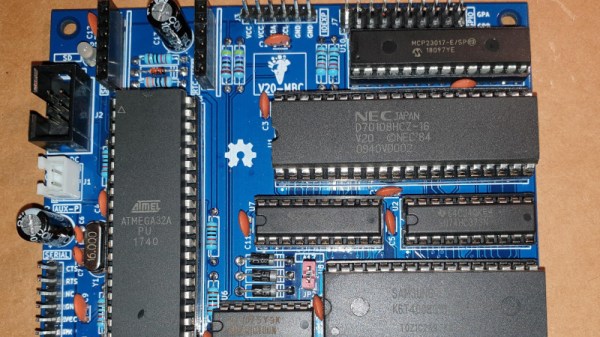

For the purpose of this article, we’ll assume the problem is the hard drive, and not another component like a power supply or SATA cable causing problems. A truly dead drive is a topic for another time, but if the drive is alive enough to show up as a block device when plugged in, then there’s hope for recovering the data. One of the USB to SATA cables available on your favorite online store is a great way to recover data. Another option is booting off a Linux DVD or flash drive, and accessing the drive in place. If you’re lucky, you can just copy your files and call it a day. If the file transfer fails because of the dying drive, or you need a full disk image, it’s time to pull out some tools and get to work. Continue reading “Tales From The Sysadmin: Impending Hard Drive Doom”