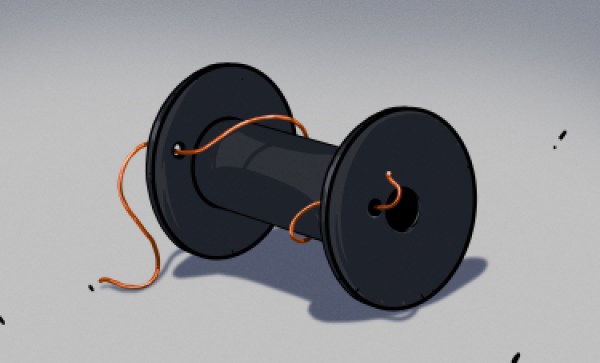

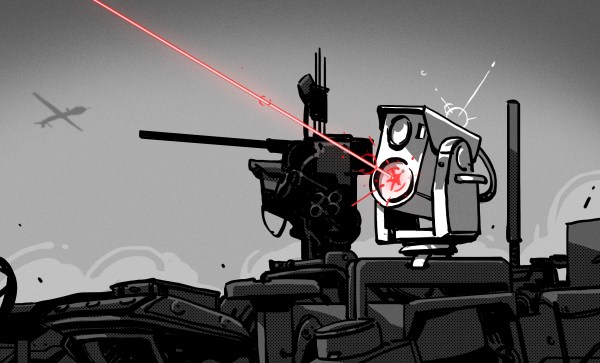

Long after the enemy forces have laid down their arms, peace accords have been signed and victories celebrated, there is still a heavy toll to be paid. Most of this comes in the form of unexploded ordnance, including landmines and the severe pollution from heavy metals and other contaminants that can make large areas risky to lethal to enter. Perhaps the most extreme example of this lasting effect is the Zone Rouge (Red Zone) in France, which immediately after the First World War came to a close comprised 1,200 square kilometers.

Within this zone, contamination with heavy metals is so heavy that some areas do not support life, while unexploded shells – some containing lethal gases – and other unexploded ordnance is found throughout the soil. To this day much of the original area remains off-limits, though injuries from old, but still very potent ordnance are common around its borders. Clean-up of the Zone Rouge is expected to take hundreds of years. Sadly, this a pattern that is repeated throughout much of the world. While European nations stumble over ordnance from its two world wars, nations in Africa, Asia and elsewhere struggle with the legacy from much more recent conflicts.

Currently, in Europe’s most recent battlefield, more mines are being laid, booby traps set and unexploded shells and other ordnance scattered where people used to live. Clearing these areas, to make them safe for a return of their inhabitants has already begun in Ukraine, but just like elsewhere in the world, it is an arduous and highly dangerous process with all too often lethal outcomes.

Continue reading “The Long Tail Of War: Finding Unexploded Ordnance Before It Finds Us”