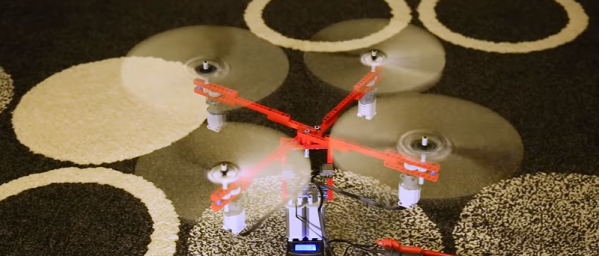

Drones (and by that we mean actual, self-flying quadcopters) have come a long way. Newer ones have cameras capable of detecting fast moving objects, but aren’t yet capable of getting out of the way of those objects. However, researchers at the University of Zurich have come up with a drone that can not only detect objects coming at them, but can quickly determine that they’re a danger and get out of the way.

The drone has cameras and accompanying algorithms to detect the movement in the span of a couple of milliseconds, rather than the 20-40 milliseconds that regular quad-copters would take to detect the movement. While regular cameras send the entire screens worth of image data to the copter’s processor, the cameras on the University’s drone are event cameras, which use pixels that detect change in light intensity and only they send their data to the processor, while those that don’t stay silent.

Since these event cameras are a new technology, the quadcopter processor required new algorithms to deal with the way the data is sent. After testing and tweaking, the algorithms are fast enough that the ‘copter can determine that an object is coming toward it and move out of the way.

It’s great to see the development of new techniques that will make drones better and more stable for the jobs they will do. It’s also nice that one day, we can fly a drone around without worrying about the neighborhood kids lobbing basketballs at them. While you’re waiting for your quadcopter delivered goods, check out this article on a quadcopter testbed for algorithm development.