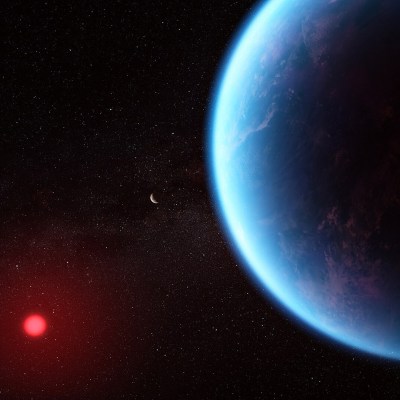

Last week, the mainstream news was filled with headlines about K2-18b — an exoplanet some 124 light-years away from Earth that 98% of the population had never even heard about. Even astronomers weren’t aware of its existence until the Kepler Space Telescope picked it out back in 2015, just one of the more than 2,700 planets the now defunct observatory was able to identify during its storied career. But now, thanks to recent observations by the James Web Space Telescope, this obscure planet has been thrust into the limelight by the discovery of what researchers believe are the telltale signs of life in its atmosphere.

Well, maybe. As you might imagine, being able to determine if a planet has life on it from 124 light-years away isn’t exactly easy. We haven’t even been able to conclusively rule out past, or even present, life in our very own solar system, which in astronomical terms is about as far off as the end of your block.

To be fair the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy researchers, lead by Nikku Madhusudhan, aren’t claiming to have definitive proof that life exists on K2-18b. We probably won’t get undeniable proof of life on another planet until a rover literally runs over it. Rather, their paper proposes that abundant biological life, potentially some form of marine phytoplankton, is one of the strongest explanations for the concentrations of dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl disulfide that they’ve detected in the atmosphere of K2-18b.

As you might expect, there are already challenges to that conclusion. Which is of course exactly how the scientific process is supposed to work. Though the findings from Cambridge are certainly compelling, adding just a bit of context can show that things aren’t as cut and dried as we might like. There’s even an argument to be made that we wouldn’t necessarily know what the signs of extraterrestrial life would look like even if it was right in front of us.

Continue reading “Life On K2-18b? Don’t Get Your Hopes Up Just Yet”