A funny thing happened on the way to the delta. The one on Jezero crater on Mars, that is, as the Perseverance rover may have captured a glimpse of the parachute that helped deliver it to the Red Planet a little over a year ago. Getting the rover safely onto the Martian surface was an incredibly complex undertaking, made all the more impressive by the fact that it was completely autonomous. The parachute, which slowed the descent vehicle holding the rover, was jettisoned well before the “Sky Crane” deployed to lower the rover to the surface. The parachute wafted to the surface a bit over a kilometer from the landing zone. NASA hasn’t confirmed that what’s seen in the raw images is the chute; in fact, they haven’t even acknowledged the big white thing that’s obviously not a rock in the picture at all. Perhaps they’re reserving final judgment until they get an overflight by the Ingenuity helicopter, which is currently landed not too far from where the descent stage crashed. We’d love to see pictures of that wreckage.

Hackaday Columns4659 Articles

This excellent content from the Hackaday writing crew highlights recurring topics and popular series like Linux-Fu, 3D-Printering, Hackaday Links, This Week in Security, Inputs of Interest, Profiles in Science, Retrotechtacular, Ask Hackaday, Teardowns, Reviews, and many more.

Retrotechtacular: A DIY Television For Very Early Adopters

By our very nature, hackers tend to get on the bandwagon of new technology pretty quickly. When something gee-whiz comes along, it’s folks like us who try it out, even if that means climbing steep learning curves or putting together odd bits of technology rather than waiting for the slicker products that will come out if the new thing takes off. But building your own television receiver in 1933 was probably pushing the envelope for even the earliest of adopters.

“Cathode Ray Television,” reprinted by the Antique Valve Museum in all its Web 1.0 glory, originally appeared in the May 27, 1933 edition of Popular Wireless magazine, and was authored by one K D Rogers of that august publication’s Research Department. They apparently took things quite seriously over there at the time, at least judging by the white lab coats and smoking materials; nothing said serious research in the 1930s quite like a pipe. The flowery language and endless superlatives that abound in the text are a giveaway, too; it’s hard to read without affecting a mental British accent, or at least your best attempt at a Transatlantic accent.

In any event, the article does a good job showing just what was involved in building a “vision radio receiver” and its supporting circuitry back in the day. K D Rogers goes into great detail explaining how an “oscillograph” CRT can be employed to display moving pictures, and how his proposed electronic system is vastly superior to the mechanical scanning systems that were being toyed with at the time. The build itself, vacuum tube-based though it was, went through the same sort of breadboarding process we still use today, progressing to a finished product in a nice wood cabinet, the plans for which are included.

It must have been quite a thrill for electronics experimenters back then to be working on something like television at a time when radio was only just getting to full market penetration. It’s a bit of a puzzle what these tinkerers would have tuned into with their DIY sets, though — the airwaves weren’t exactly overflowing with TV broadcasts in 1933. But still, someone had to go first, and so we tip our hats to the early adopters who figured things out for the rest of us.

Thanks to [BT] for the tip.

The Virtue Of Wires In The Age Of Wireless

We ran an article this week about RS-485, a noise resistant differential serial multidrop bus architecture. (Tell me where else you’re going to read articles like that!) I’ve had my fun with RS-485 in the past, and reading this piece reminded me of those days.

You see, RS-485 lets you connect a whole slew of devices up to a single bundle of Cat5 cable, and if you combine it with the Modbus protocol, you can have them work together in a network. Dedicate a couple of those Cat5 lines to power, and it’s the perfect recipe for a home, or hackerspace, small-device network — the kind of things that you, and I, would do with WiFi and an ESP8266 today.

Wired is more reliable, has fewer moving parts, and can solve the “how do I get power to these things” problem. It’s intrinsically simpler: no radios, just serial data running as voltage over wires. But nobody likes running cable, and there’s just so much more demo code out there for an ESP solution. There’s an undeniable ease of development and cross-device compatibility with WiFi. Your devices can speak directly to a computer, or to the whole Internet. And that’s been the death of wired.

Still, some part of me admires the purpose-built simplicity and the bombproof nature of the wired bus. It feels somehow retro, but maybe I’ll break out some old Cat5 and run it around the office just for old times’ sake.

PCB Thermal Design Hack Gets Hot And Heavy

Thanks to the relatively recent rise of affordable board production services, many of the people reading Hackaday are just now learning the ropes of PCB design. For those still producing the FR4 equivalent of “Hello World”, it’s accomplishment enough that all the traces go where they’re supposed to. But eventually your designs will become more ambitious, and with this added complexity will naturally come new design considerations. For example, how do you keep a PCB from cooking itself in high current applications?

It’s this exact question that Mike Jouppi hoped to help answer when he hosted last week’s Hack Chat. It’s a topic he takes very seriously, enough that he actually started a company called Thermal Management LLC dedicated to helping engineers cope with PCB thermal design issues. He also chaired the development of IPC-2152, a standard for properly sizing board traces based on how much current they’ll need to carry. It isn’t the first standard that’s touched on the issue, but it’s certainly the most modern and comprehensive.

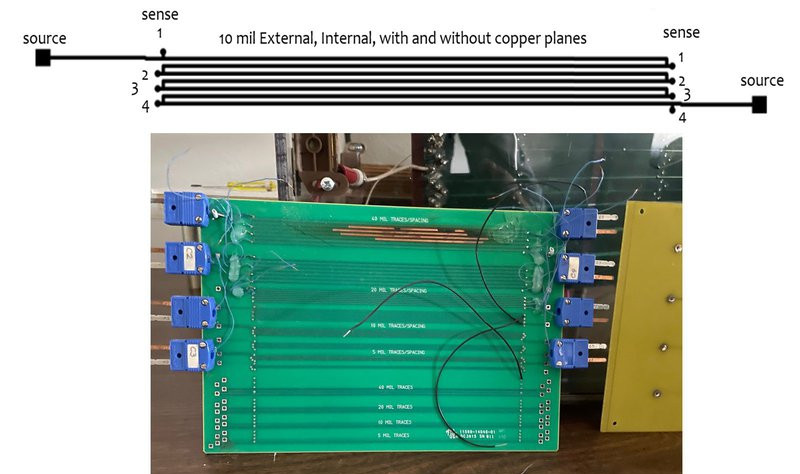

It’s common for many designers, who can be referencing data that in some cases dates back to the 1950s, to simply oversize their traces out of caution. Often this is based on concepts that Mike says his research has found to be inaccurate, such as the assumption that the inner traces of a PCB tend to run hotter than those on the outside. The new standard is designed to help designers avoid these potential pitfalls, though he notes that it’s still an imperfect analog for the real-world; additional data such as mounting configuration needs to be taken into consideration to get a better idea of a board’s thermal properties.

It’s common for many designers, who can be referencing data that in some cases dates back to the 1950s, to simply oversize their traces out of caution. Often this is based on concepts that Mike says his research has found to be inaccurate, such as the assumption that the inner traces of a PCB tend to run hotter than those on the outside. The new standard is designed to help designers avoid these potential pitfalls, though he notes that it’s still an imperfect analog for the real-world; additional data such as mounting configuration needs to be taken into consideration to get a better idea of a board’s thermal properties.

Even with such a complex topic, there’s some tips that are widely applicable enough to keep in mind. Mike says the thermal properties of the substrate are always going to be poor compared to copper, so using internal copper planes can help conduct heat through the board. When dealing with SMD parts that produce a lot of heat, large copper plated vias can be used to create a parallel thermal path.

Towards the end of the Chat, Thomas Shaddack chimes in with an interesting idea: since the resistance of a trace will increase as it gets hotter, could this be used to determine the temperature of internal PCB traces that would otherwise be difficult to measure? Mike says the concept is sound, though if you wanted to get an accurate read, you’d need to know the nominal resistance of the trace to calibrate against. Certainly something to keep in mind for the future, especially if you don’t have a thermal camera that would let you peer into a PCB’s inner layers.

While the Hack Chats are often rather informal, we noticed some fairly pointed questions this time around. Clearly there were folks out there with very specific issues that needed some assistance. It can be difficult to address all the nuances of a complex problem in a public chat, so in a few cases we know Mike directly reached out to attendees so he could talk them through the issues one-on-one.

While we can’t always promise you’ll get that kind of personalized service, we think it’s a testament to the unique networking opportunities available to those who take part in the Hack Chat, and thank Mike for going that extra mile to make sure everyone’s questions were answered to the best of his ability.

The Hack Chat is a weekly online chat session hosted by leading experts from all corners of the hardware hacking universe. It’s a great way for hackers connect in a fun and informal way, but if you can’t make it live, these overview posts as well as the transcripts posted to Hackaday.io make sure you don’t miss out.

Hackaday Podcast 163: Movie Sound, Defeating Dymo DRM, 3DP Guitar Neck, Biometrics Bereft Of Big Brother

Join Hackaday Editor-in-Chief Elliot Williams and Assignments Editor Kristina Panos as we spend an hour or so dissecting some of the more righteous hacks and projects from the previous week. We’ll discuss a DIY TPM module that satisfies Windows 11, argue whether modern guts belong in retrocomputer builds even if it makes them more practical, and marvel at the various ways that sound has been encoded on film. We’ll also rock out to the idea of a 3D-printed guitar neck, map out some paths to defeating DYMO DRM, and admire a smart watch that has every sensor imaginable and lasts 36+ hours on a charge. Finally, we’ll sing the praises of RS-485 and talk about our tool collections that rival our own Dan Maloney’s catalogue of crimpers.

Check out the links below if you want to follow along, and as always, tell us what you think about this episode in the comments below!

Direct download the show, so you can listen on the go!

This Week In Security: Vulnerable Boxes, Government Responses, And New Tools

The Cyclops Blink botnet is thought to be the work of an Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) from Russia, and seems to be limited to Watchguard and Asus devices. The normal three and four letter agencies publicized their findings back in February, and urged everyone with potentially vulnerable devices to go through the steps to verify and disinfect them if needed. About a month later, in March, over half the botnet was still online and functioning, so law enforcement took a drastic step to disrupt the network. After reverse-engineering the malware itself, and getting a judge to sign off on the plan, the FBI remotely broke in to 13 of the Watchguard devices that were working as Command and Control nodes. They disinfected those nodes and closed the vulnerable ports, effectively knocking a very large chunk of the botnet offline.

The vulnerability in WatchGuard devices that facilitated the Botnet was CVE-2022-23176, a problem where an “exposed management access” allowed unprivileged users administrative access to the system. That vague description sounds like either a debugging interface that was accidentally included in production, or a flaw in the permission logic. Regardless, the problem was fixed in a May 2021 update, but not fully disclosed. Attackers apparently reversed engineered the fix, and used it to infect and form the botnet. The FBI informed WatchGuard in November 2021 that about 1% of their devices had been compromised. It took until February to publish remediation steps and get a CVE for the flaw.

This is definitely non-ideal behavior. More details and a CVE should have accompanied the fix back in May. As we’ve observed before, obscurity doesn’t actually prevent sophisticated actors from figuring out vulnerabilities, but it does make it harder for users and security professionals to do their jobs. Continue reading “This Week In Security: Vulnerable Boxes, Government Responses, And New Tools”

Whales Help Scientists Investigate The Mystery Of Menopause

Menopause is the time of life when menstrual periods come to a halt, and a woman is no longer able to bear children. The most obvious cause of menopause is when the ovaries run out of eggs, though it can also be caused by a variety of other medical processes. While menopause is in many ways well-understood, the biological reason for menopause, or the way in which it evolved in humanity remains a mystery. The process was once thought to be virtually non-existent in the animal kingdom, raising further questions.

Surprisingly recently, however, scientists began to learn that humans are not alone in this trait. Indeed, a small handful of sea-going mammals also go through this unique and puzzling process.

Continue reading “Whales Help Scientists Investigate The Mystery Of Menopause”