Starting your garden indoors helps to ensure large yields. This is because the plants get a head start before it’s warm enough for them to be put in the ground. But the process involves a fair amount of labor, ensuring that the lights are turned on and off at the right times each day, and that the temperature for germination and growth, as well as humidity, hit a certain target. It’s obvious that a bit of automation would be nice, and this Arduino-based garden nursery does just that. One of the things that sets this project apart is that it shows you how to go from an empty room to the bounty of plant starters seen here.

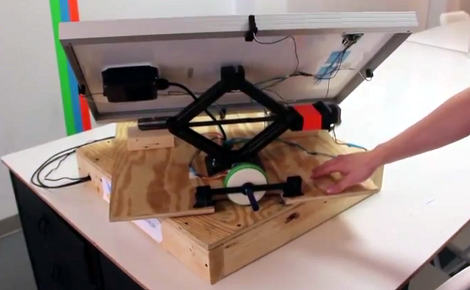

For the most part the equipment is what you’d expect, seed trays and covers, tray warming mats, and fluorescent light fixtures. the whole thing is given a small footprint thanks to an adjustable shelving unit. The Arduino is used in conjunction with a Sprout Board to add connectivity for switching the lights and warming mats. This is just a matter of driving a relay to switch mains voltage and can take any number of forms, including this home automation project we saw the other day.

[Thanks Tom]