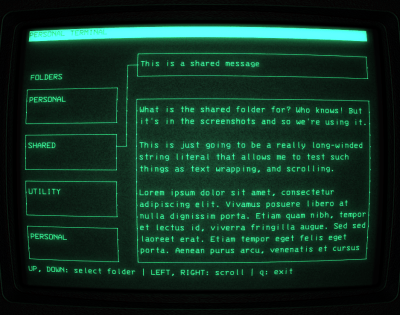

Not every programmer likes creating GUI code. Most hacker types don’t mind a command line interface, but very few ordinary users appreciate them. However, if you write command line programs in Python, Gooey can help. By leveraging some Python features and a common Python idiom, you can convert a command line program into a GUI with very little effort.

The idea is pretty simple. Nearly all command line Python programs use argparse to simplify picking options and arguments off the command line as well as providing some help. The Gooey decorator picks up all your options and arguments and creates a GUI for it. You can make it more complicated if you want to change specific things, but if you are happy with the defaults, there’s not much else to it.

At first, this article might seem like a Python Fu and not a Linux Fu, since — at first — we are going to focus on Python. But just stand by and you’ll see how this can do a lot of things on many operating systems, including Linux.

Continue reading “Linux Fu: Python GUIs For Command Line Programs (Almost) Instantly”