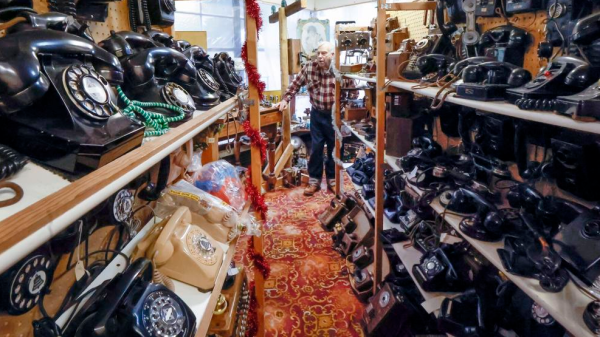

Telephones. We’ve got a few around the place, and some may remember all the weird and wonderful varieties produced over the years. But, vintage phone dealers [Ron and Mary Knappen] may have a few too many. With a large 41,000 sqft property, at least three farm buildings, and no fewer than 33 semi-trailers loaded to busting with racks of phones, the retiring couple have a job sorting it all out and finding someone passionate enough to take over this once-strong business.

Technology has moved on somewhat since 1971 when they got into the retro business, and there are only so many period dramas being produced that could make a dent in a collection of a thousand steel desk phones. Nobody seems interested in taking on their business, so they are concentrating on emptying that large property in order to sell it, but the fate of the crazy number of other storage locations seems uncertain. Perhaps, other than a few museums around the world purchasing a few, this collection really is likely heading to the recyclers.

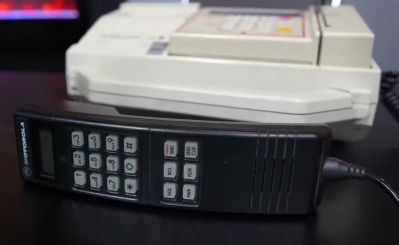

So what can we do with a vintage phone in this modern era? Here’s a primer to get you started. How about going cellular? Or maybe just add them to your existing designer collection?

Thanks to [Jeremy] and Adafruit for the tip!