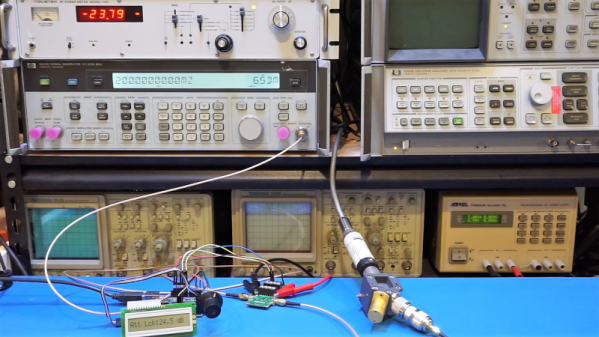

[Kerry Wong] comes across the coolest hardware, and always manages to do something interesting with it. His widget du jour is an old demo board for a digital RF attenuator chip, which can pad a signal in discrete steps according to the settings of some DIP switches. [Kerry]’s goal: forget the finger switch-flipping and bring the attenuator under Arduino control.

As usual with his videos, [Kerry] gives us a great rundown on the theory behind the hardware he’s working with. The chip in question is an interesting beast, an HMC624LP4E from Hittite, a company that was rolled into Analog Devices in 2014. The now-obsolete device is a monolithic microwave integrated circuit (MMIC) built on a gallium arsenide substrate rather than silicon, and attenuates DC to 6-GHz signals in 64 steps down to -31.5 dBm. After a functional check of the board using the DIP switches, he whipped up a quick Arduino project to control the chip with its built-in serial interface. It’s just a prototype for now, but spinning the encoder is a lot handier than flipping switches, and once this is boxed up it’ll make a great addition to [Kerry]’s RF bench.

If this video puts you in an RF state of mind, check out some of [Kerry]’s other videos, like this one about temperature-compensated crystal oscillators, or the mysteries of microwave electronics.

Continue reading “Digital Attenuator Goes From Manual To Arduino Control”