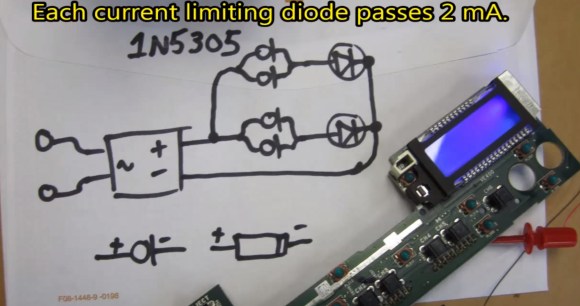

Not that this happens often, but what do you do when faced with a repair where you don’t know the power source but you do know you have to drive LED backlighting? When faced with this dilemma [Eric Wasatonic’s] solution was to design for ambiguity. In this interesting hack repair [Eric] needed to restore backlighting for an old car stereo LCD display. First he guaranteed he was working with a DC power source by inserting a small full-wave bridge rectifier. Then knowing he needed 4 mA to power each LED for backlighting he used some 1978 vintage current limiting diodes designed to pass 2mA each regardless of voltage source, within limits of course.

Sure this is a simple hack repair but worthy of being included in anyone’s bag of tricks. Like most hacks there is always knowledge to be gained. [Eric] shares a second video where he uses a curve tracer and some datasheets to understand how these old parts actually tick. These old 1N5305 current limiting diode regulators are simply constructed from a JFET with an internal feedback resistor to its gate which maintains a fixed current output. To demonstrate the simplicity of such a component, [Eric] constructs a current limiting circuit using a JFET and feedback potentiometer then confirms the functionality on a curve tracer. His fabricated simulation circuit worked perfectly.

There was a little money to be made with this repair which is always an added bonus, and the recipient never reported back with any problems so the fix is assumed successful. You can watch the two videos linked after the break, plus it would be interesting to hear your thoughts on what could have been done differently given the same circumstances.