Conceptually, radar is pretty simple: send out a radio wave and time how long it takes to get back via an echo. However, in practice, there are a number of trade-offs to consider. For example, producing a long pulse has more energy and range, but limits how close you can see and also the system’s ability to resolve objects that are close to each other. Pulse compression uses a long transmission that varies in frequency. Reflected waves can be reconstituted to act more like a short pulse since there is information about the exact timing of the reflected energy. [Henrik] didn’t want to make things too easy, so he decided to build a pulse compression radar that operates at 6 GHz.

In all fairness, [Henrik] is no neophyte when it comes to radar. He’s made several more traditional devices using a continuous wave architecture. However, this type of radar is only found in a few restricted applications due to its inherent limitations. The new system can operate in a continuous wave mode, but can also code pulses using arbitrary waveforms.

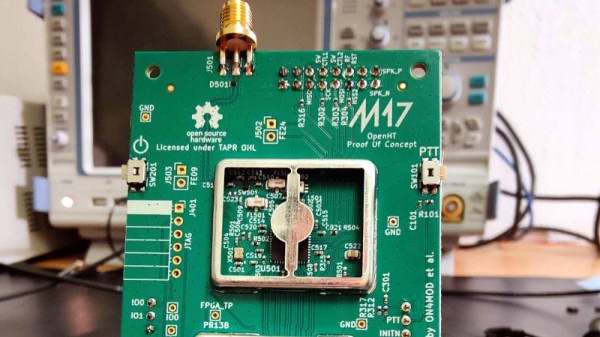

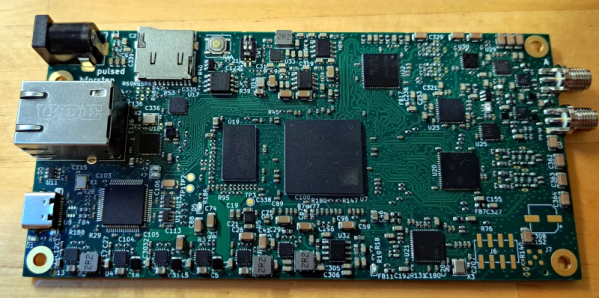

Some design choices were made to save money. For example, the transmitter and receiver have limited filtering. In addition, the receiver isn’t a superheterodyne but more of a direct conversion receiver. The signal processing is made much easier by using a Zynq FPGA with a dual-core ARM CPU onboard. These were expensive from normal sources but could be had from online Chinese vendors for about $17. The system could boot Linux, although that’s future work, according to [Henrik].

At 6 GHz, everything is harder. Routing the PCB for DDR3 RAM is also tricky, but you can read how it was done in the original post. To say we were impressed with the work would be an understatement. We bet you will be too.

Radar has come a long way since World War II and is in more places than you might guess. We hate to admit it, but we’d be more likely to buy a ready-made radar module if we needed it.