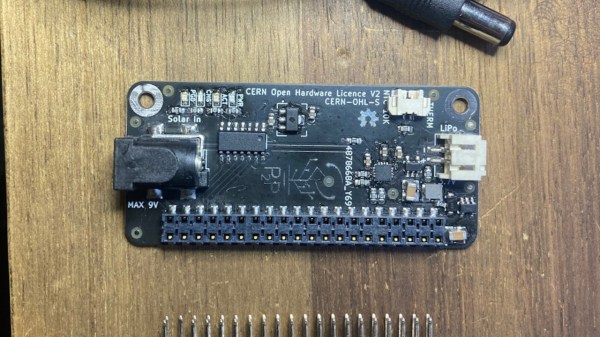

A Pi Zero doesn’t need much to sustain itself, and it’s projects like the PhotonPower Zero that remind us of it its low appetite when we need this reminder most. The PhotonPower Zero board lets you power a Pi Zero board from a solar cell, with a LiIon backup, and a microcontroller for power management. Created by [David Murray], this board’s been a perfect solution for quite a few projects of his, and now he is sharing the design so that we can create outdoor-suited devices as easily as he’s been able to.

Tested for months in Australian summer and winter conditions alike, the design pulls no punches and has everything you might need. Like any self-respecting power addon, it has a management microcontroller for going as low-power as you’d like, communicating the battery data to the Pi Zero, and being able to safely shut it down when needed. If you fancy what this board does, [David Murray] tells you all, both in the video and in the associated posts!

One of the best parts about this board is that it’s fully open-source – schematics, KiCad PCB source files, and even 3D designs are available in the GitHub repo. You could source all the parts right now and build a fleet of solar-powered Zeros, and if you want the hard parts to be done for you, there’s a Kickstarter campaign that lets you get a PhotonPower Zero board without self-assembly. We’ve covered similar boards before – powering a Pi Zero isn’t lost art, and, there’s a lot to learn from this project specifically. Such boards are especially tempting, given that the latest Pi Zero W 2 is the most efficient Pi Zero to date – outdoor-capable 24/7 powered devices with a fair bit of CPU have never been this close!

Continue reading “PhotonPower Zero For Effortless Solar Pi Zero Projects”