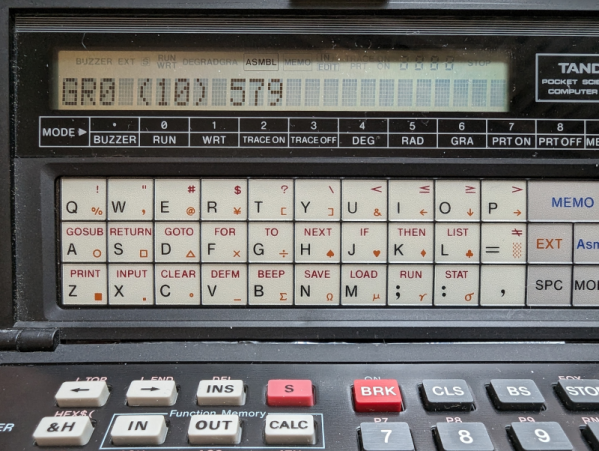

The TRS-80 Model 100 was released in 1983, featuring an 80C85 CPU that can run at 5 MHz, but only runs at a hair under 2.5 MHz, due to 1:2 divider on the input clock. Why cut the speed in half? It has a lot to do with the focus of the M100 on being a portable device with low power usage. Since the CPU can run at 5 MHz and modding these old systems is a thing, we got a ready-made solution for the TRS-80 M100, as demonstrated by [Ken] in a recent video using one of his ‘daily driver’ M100s.

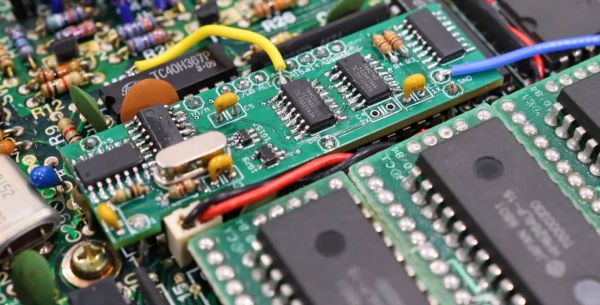

This uses the board design from the [Bitchin100] website, along with the M100 ROM image, as one does not simply increase the CPU clock on these old CPUs. The issue is namely that along with the CPU clock, connected components on the CPU bus now have to also run at those speeds, and deal with much faster access speed requirements. This is why beyond the mod board that piggybacks on top of the MPU package, it’s also necessary to replace the system ROM chip (600 ns) with a much faster one, like the Atmel AT27C256R (45 ns), which of course requires another carrier board to deal with incompatible pinouts.

Continue reading “Doubling The CPU Speed Of The TRS-80 Model 100 With A Mod Board”