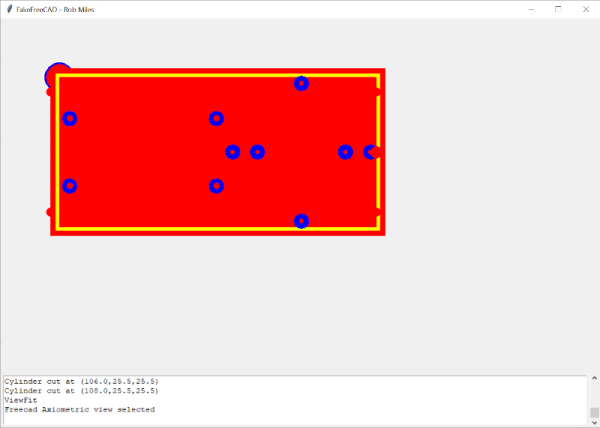

As the leaves fall from the trees here in the Northern Hemisphere, we are greeted with a clear view of the branches and limbs that make up the skeleton of the tree. [Nicolas McDonald] made a simple observation while looking at trees, that the sum of the cross-sectional area is conserved when a branch splits. This observation was also made by Leonardo Da Vinci (according to Pamela Taylor’s Da Vinci’s Notebooks). Inspired by the observation, [Nicolas] decided to model a tree growing for his own curiosity.

The simulation tries to approximate how trees spread nutrients. The nutrients travel from the roots to the limbs, splitting proportionally to the area. [Nicolas’] model only allows for binary splits but some plants split three ways rather than just two ways. The decision on where to split is somewhat arbitrary as [Nicolas] hasn’t found any sort of rule or method that nature uses. It ended up just being a hardcoded value that’s multiplied by an exponential decay based on the depth of the branch. The direction of the split is determined by the density of the leaves, the size of the branch, and the direction of the parent branch. To top it off, a particle cloud was attached at the end of each branch past a certain depth.

By tweaking different parameters, the model can generate different species like evergreens and bonsai-like trees. The code is hosted on GitHub and we’re impressed by how small the actual tree model code is (about 250 lines of C++). The power of making an observation and incorporating it into a project is clear here and the results are just beautiful. If you’re looking for a bit more procedurally generation in your life, check out this medieval city generator.