The handheld screw driver is a wonderful tool. We’re often tempted to reach for its beefier replacement, the power drill/driver. But the manually operated screw driver has an extremely direct feedback mechanism; the only person to blame when the screw strips or is over-torqued is you. This is a near-perfect tool and when you pull the right screwdriver from the stone you will truly be the ruler of the fastener universe.

A Bit of Screw Driver History:

In order to buy a good set of screw drivers, it is important to understand the pros and cons of the geometry behind it. With a bit of understanding, it’s possible to look at a screw driver and tell if it was built to turn screws or if it was built to sell cheap.

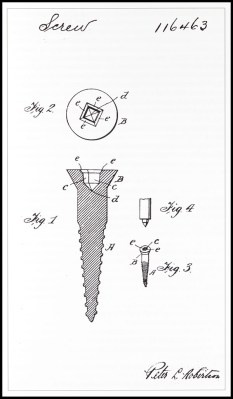

Screw heads were initially all slotted. This isn’t 100 percent historically accurate, but when it comes to understanding why the set at the big box store contains the drivers it does, it helps. (There were a lot of square headed screws back in the day, we still use them, but not as much.)

Flat head screws could be made with a slitting saw, hack saw, or file. The flat-head screw, at the time, was the cheapest to make and had pretty good torque transfer capabilities. It also needed hand alignment, a careful operator, and would almost certainly strip out and destroy itself when used with a power tool.

These shortcomings along with the arrival of the industrial age brought along many inventions from necessity, the most popular being the Phillips screw head. There were a lot of simultaneous invention going on, and it’s not clear who the first to invent was, or who stole what from who. However, the Philips screw let people on assembly lines turn a screw by hand or with a power tool and succeed most of the time. It had some huge downsides, for example, it would cam out really easily. This was not an original design intent, but the Phillips company said, “to hell with it!” and marketed it as a feature to prevent over-torquing anyway.

The traditional flathead and the Phillips won over pretty much everyone everywhere. Globally, there were some variations on the concept. For example, the Japanese use JST standard or Posidriv screws instead of Philips. These do not cam out and let the user destroy a screw if they desire. Which might show a cultural difference in thinking. That aside, it means that most of the screws intended for a user to turn with a screw driver are going to be flat-headed or Philips regardless of how awful flat headed screws or Philips screws are.

Continue reading “Hacker’s Toolbox: The Handheld Screw Driver”