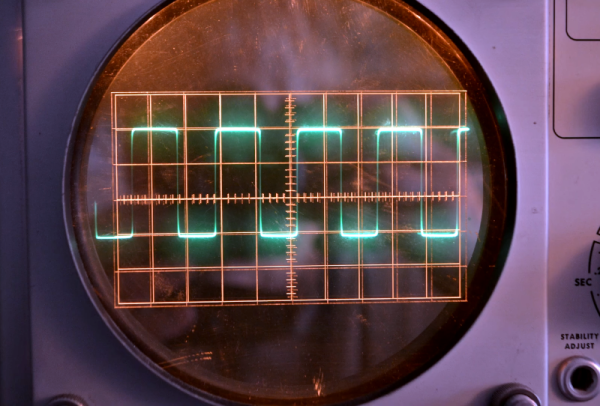

Oscilloscopes are great for measuring the time and voltage information of a signal. Some old scopes don’t have much in the way of markings on the CRT, although eventually, we started seeing scales that allowed you to count squares easily. Early scopes had marks on the glass or plastic over the CRT, but as [Vintage TEK Museum] points out, this meant for best accuracy, you had to look directly at the CRT. If you were at an angle horizontally or vertically, the position of the trace would appear to move concerning the lines on the screen. You can see the effect in the video below.

The simple solution was to mark directly into the phosphor, which minimized the effect. Before that was possible, [Bob Anderson] invented a clever solution, although Tektronix didn’t produce any scopes using it for some reason. The idea was the virtual oscilloscope graticule, and it was quite clever.

The idea was to put the graticule on a semi-reflective mirror. Looking through the assembly, you would actually see the trace and the reflection of the graticule in the mirror. The resulting image is perfectly aligned if the assembly is constructed properly. You can, at some angles, see both the front and reflected graticules.

According to the video, management was not impressed because someone other than [Anderson] showed a poor-quality prototype to them. By 1962, the graticule in the phosphor took over, and there was no need for [Anderson’s] clever invention.

These days, a graticule is just bits on the screen. Even if you roll your own.