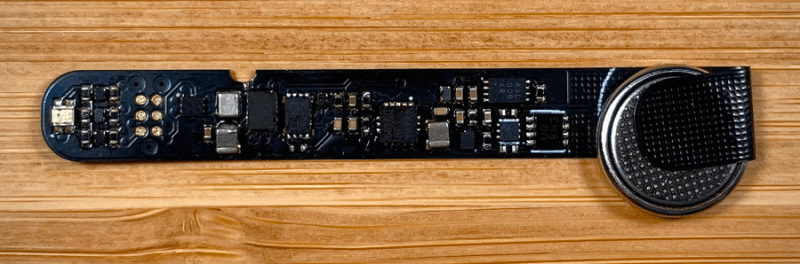

Long before the current smartwatch craze, Texas Instruments released the eZ430-Chronos. Even by 2010s standards, it was pretty clunky. Its simple LCD display and handful of buttons also limited what kind of “smart” tasks it could realistically perform. But it did have one thing going for it: its SDK allowed users to create a custom firmware tailored to their exact specifications.

It’s been nearly a decade since we’ve seen anyone dust off the eZ430-Chronos, but that didn’t stop [ogdento] from turning one into a custom alert device for a sick family member. A simple two-button procedure on the watch will fire off emails and text messages to a pre-defined list of contacts, all without involving a third party or have to pay for a service contract. Perhaps most importantly, the relatively energy efficient eZ430 doesn’t need to be recharged weekly or even daily as would be the case for a modern smartwatch.

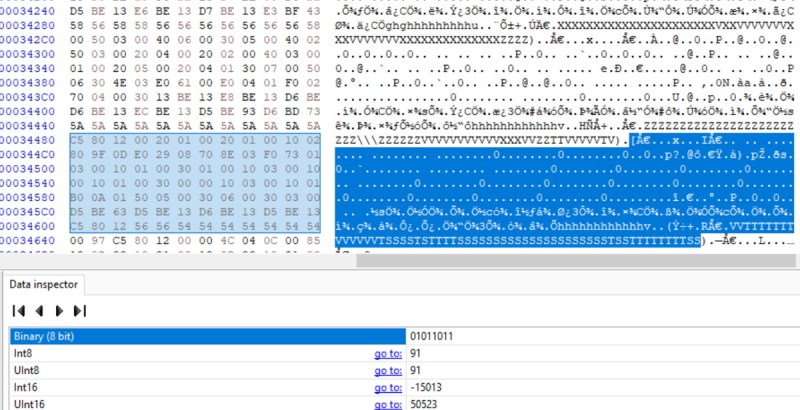

To make the device as simple as possible, [ogdento] went through the source code for the stock firmware and commented out every function beyond the ability to show the time. With the watch’s menu stripped down to the minimum, a new alert function was introduced that can send out a message using the device’s 915 MHz CC1101 radio.

The display even shows “HELP” next to the appropriate button so there’s no confusion. A second button press is required to send the alert, and there’s even a provision for canceling it should the button be pressed accidentally.

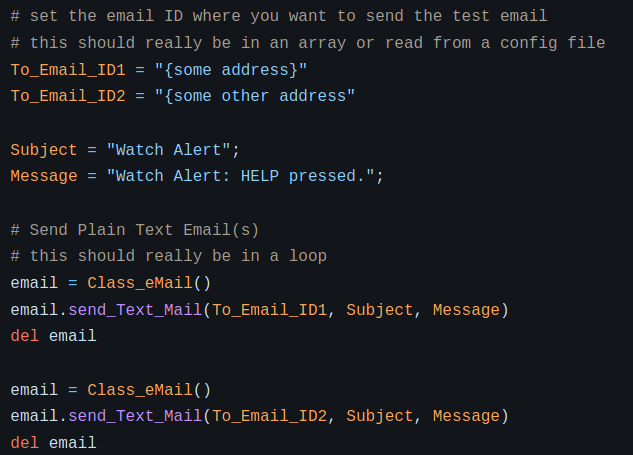

On the receiving side, [ogdento] is using a Raspberry Pi with its own CC1101 radio plugged into the USB port. When the Python scripts running on the Pi picks up the transmission coming from the eZ430 it starts working through a list of recipients to send messages to. A quick look at the source code shows it would be easy to provide your own contact list should you want to put together your own version of this system.

We’ve seen custom alert hardware before, but like [ogdento] points out, using the eZ430-Chronos provides a considerable advantage in that its a turn-key platform. It’s comfortable to wear, reliable, and fairly rugged. While some would argue against trusting independently developed code for such a vital task, at least the hardware is a solved problem.