[Jochen Alt] is on a roll. We just covered his ball-balancing robot, Paul, only to find his phenomenal six-DOF robot arm in full retro style. Its name is “Walter” and it’s done up in DDR style (the former East Germany), in painted, 3D-printed plastic. The full design and build documents are an absolutely amazing resource if you’re into robot arm or legs.

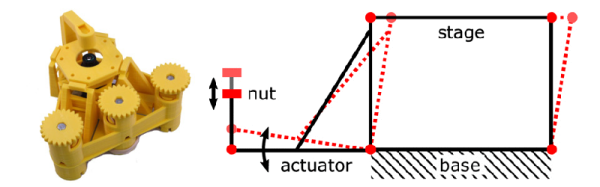

In particular, the sections on trajectory planning and kinematics are fantastic. If you’re interested in robot motion planning by Bezier curves, you know where to go. (We’ve always wanted a Bezier-curve 3D printer slicer, but that’s another story.) The construction is also top-notch here, and the attention to detail that went into this arm is phenomenal. It’s all done with stepper motors and geared belts, which allow each of Walter’s joints to be driven by a motor that’s one joint further upstream than would be the case if it were designed with servos. [Jochen] even went so far as to expose the belt in some places to show off the gearing. Walter is worth checking out.

Even if you’ll never build such a fancy robot arm, you should read through the docs just to appreciate all of the thought and work that went into this very refined and simple-from-the-outside design. If you’d like to start out on the simple side of the spectrum, check out these robot arms made of office supplies or a desk lamp. Once you’re ready for your second arm project this short list, some of which [Jochen] mention in his writeup, should get you up and grasping. And do check out his balancing bot, Paul.