If you think at all about liquid crystals, you probably think of display technology. However, researchers have worked out a way to use an ink-jet-like process to 3D print iridescent colors using a liquid crystal elastomer. The process can mimic iridescent coloring found in nature and may have applications in things as diverse as antitheft tags, art objects, or materials with very special optical properties.

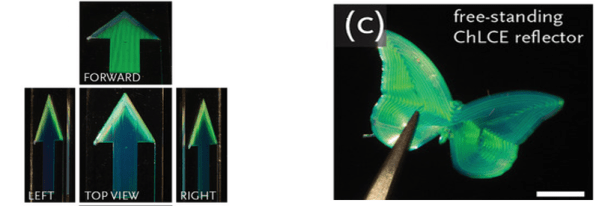

For example, one item created by the team is an arrow that only appears totally green when viewed from a certain angle. The optical properties depend on the thickness of the material which, being crystalline, self-organizes. Controlling the speed of deposition changes the thickness of the material which allows the printer to tune its optical properties.

The ink doesn’t sound too exotic to create, although the chemicals in it are an alphabet soup of unpronounceable organic compounds. At least they appeared available if you know where to shop for exotic chemicals.

The iridescent coloring is common in nature, so art objects like butterfly wings are natural with this method. While inkjet printers aren’t common in the hacker community, they aren’t that hard to create, so this seems like it would be repeatable in a garage lab.

Liquid crystals have all kinds of interesting properties and we wonder if this material would help you print those sorts of things. If you want to experiment, we have seen a few hacked inkjet printers.

Thanks [jscotta] for the tip.