If you would like to make a 3D print stronger, just add more material. Increase the density of the infill, or add more perimeters. The problem you’ll encounter though is that you don’t need to add more plastic everywhere, only in the weak areas of the part that will be subjected to the most stress. Studying where parts will be the weakest is the domain of finite element analysis, and yes, you can do it in Fusion 360. With the right techniques, you can make a stronger part on your 3D printer, and [Stefan] is here to show you how to do it.

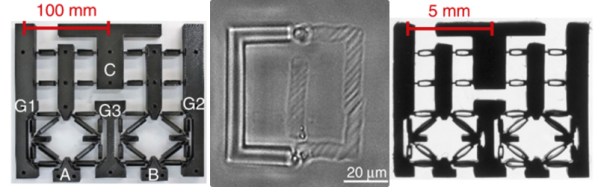

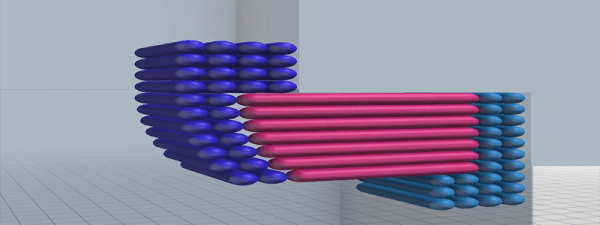

The inspiration for this build comes from [Adrian Bowyer]’s blog, where he talks about adding ‘fibers’ to the interior of 3D printed objects to increase strength. These ‘fibers’ aren’t really fibers at all, but long, thin, cylindrical voids. The theory of this is that the slicer will interpret this as a hole and place perimeters around these voids, effectively increasing the density of the infill in a local area in the print. Combine this with finite element analysis, and you get a part that is stronger where it needs to be, and doesn’t waste plastic.

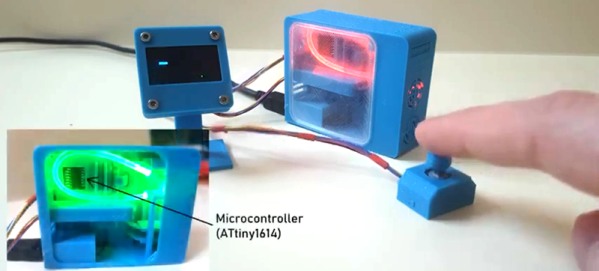

However, there is an easier way. Fusion 360 and ANSYS Finite Element Simulation are both free-ish tools that allow for some amount of finite element analysis on an imported 3D object. This can be used to find the weakest part of any 3D print, and it can this can be exported as a 3D mesh. Slic3r has a modifier mesh function, and combining this finite element analysis mesh (printed at 100% infill) with the original part (printed at 10% or so infill) results in something that’s strong where it needs to be, doesn’t waste plastic, and is much easier to set up than [Adrian Bowyer]’s ‘fiber’ technique.

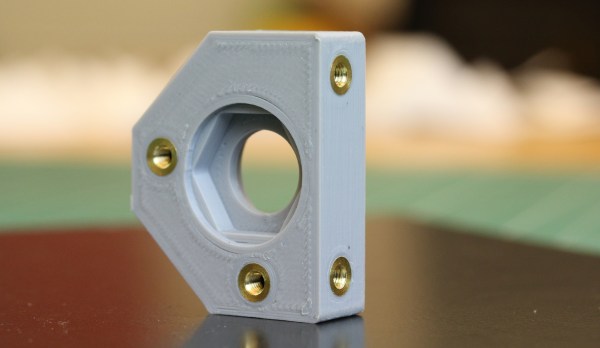

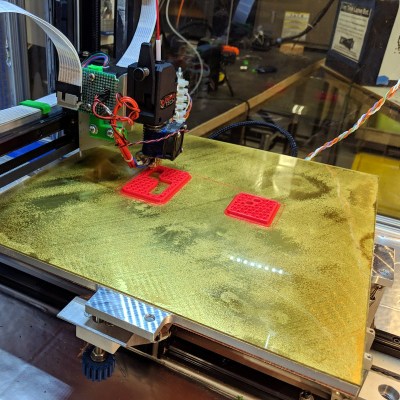

After printing a few 3D printed hooks with varying degrees and techniques of infill, [Stefan] found the baseline of 2 perimeters failed in a test hook at about 50kg load. The Smart Infill hook failed at about 100kg. Not bad, and the fancy-pants hook only weighs about 30% more.

You can check out a video of the entire toolchain and testing below. Thanks [Keith] for sending this one in.

Continue reading “Finite Element Analysis Results In Smart Infill” →