Hackers can be a diverse bunch. My old hackerspace had folks ranging from NSA employees (ahem, independent security contractors) to space-probe pilots to anarchist vegan punks. And we all got along because we shared a common love for what we’re doing. One summer night we were out late in Adams Morgan and my vegan-punk friend reaches into the trash can and pulls out a discarded pepperoni Jumbo Slice.

“Wait a minute! Vegans don’t eat pepperoni pizza with cheese.” But my friend was a “freegan” — a vegan who, for ethical reasons, won’t buy meat or milk but who also won’t turn it down if it’s visibly going to waste. It’s actually quite a practical and principled moral proposal if you think about it: he’s not contributing to the use of animals that he opposes, but he gets to have a slice of pizza just the same. And fishing a slice of pizza, in a cardboard container, off the top of the trashcan isn’t as gross as you’d imagine, although it pays to be picky.

A Fracker is Born

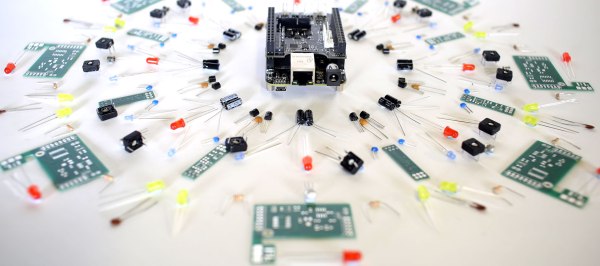

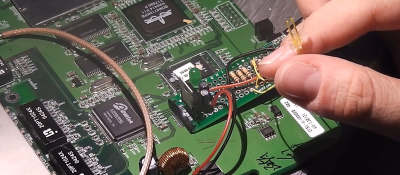

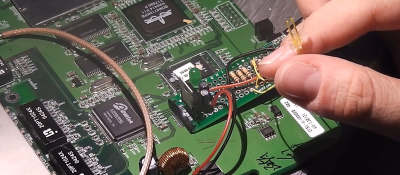

That was the night that we realized we all had something deeper in common: we were all “frackers”. If you’ve been around hackers long enough, you’ll have noticed this tendency, but maybe you’ve never put a name to it. Tearing something apart, even if you might break it in the process, isn’t a problem if you fished it out of the e-waste stream to begin with. If you’re able to turn it into something, so much the better. It’s all upside. Need practice de-soldering tricky ICs? Looking for a cheap target to learn reverse engineering on? Off to the trashcan! No hack is too dirty, no method too barbaric. It’s already junk, and you’re a fracker.

Do you have a junk shelf where you keep old heatsinks in case you need to cut some up and use it? Have you used a heat gun more frequently for harvesting parts than for stripping paint? Do you know that certain satisfaction that you get from pulling some old tech out of the junk pile and either fixing it up again or, better yet, making it do something else? You might just be a fracker too.

Do you have a junk shelf where you keep old heatsinks in case you need to cut some up and use it? Have you used a heat gun more frequently for harvesting parts than for stripping paint? Do you know that certain satisfaction that you get from pulling some old tech out of the junk pile and either fixing it up again or, better yet, making it do something else? You might just be a fracker too.

Continue reading “Frackers: Inside The Mind Of The Junk Hacker” →