X-ray crystallography, like mass spectroscopy and nuclear spectroscopy, is an extremely useful material characterization technique that is unfortunately hard for amateurs to perform. The physical operation isn’t too complicated, however, and as [Farben-X] shows, it’s entirely possible to build an X-ray diffractometer if you’re willing to deal with high voltages, ancient X-ray tubes, and soft X-rays.

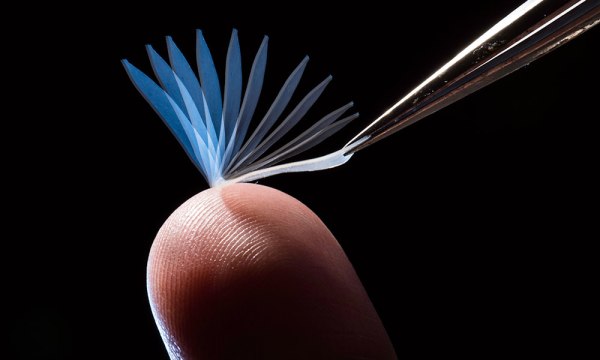

[Farben-X] based his diffractometer around an old Soviet BSV-29 structural analysis X-ray tube, which emits X-rays through four beryllium windows. Two ZVS drivers power the tube: one to drive the electron gun’s filament, and one to feed a flyback transformer and Cockroft-Walton voltage multiplier which generate a potential across the tube. The most important part of the imaging system is the X-ray collimator, which [Farben-X] made out of a lead disk with a copper tube mounted in it. A 3D printer nozzle screws into each end of the tube, creating a very narrow path for X-rays, and thus a thin, mostly collimated beam.

To get good diffraction patterns from a crystal, it needed to be a single crystal, and to actually let the X-ray beam pass through, it needed to be a thin crystal. For this, [Farben-X] selected a sodium chloride crystal, a menthol crystal, and a thin sheet of mica. To grow large salt crystals, he used solvent vapor diffusion, which slowly dissolves a suitable solvent vapor in a salt solution, which decreases the salt’s solubility, leading to very slow, fine crystal growth. Afterwards, he redissolved portions of the resulting crystal to make it thinner.

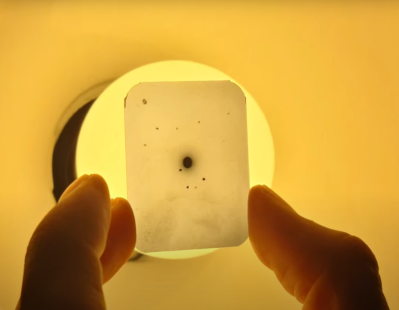

For the actual experiment, [Farben-X] passed the X-ray beam through the crystals, then recorded the diffraction patterns formed on a slide of X-ray sensitive film. This created a pattern of dots around the central beam, indicating diffracted beams. The mathematics for reverse-engineering the crystal structure from this is rather complicated, and [Farben-X] hadn’t gotten to it yet, but it should be possible.

We would recommend a great deal of caution to anyone considering replicating this – a few clips of X-rays inducing flashes in the camera sensor made us particularly concerned – but we do have to admire any hack that coaxed such impressive results out of such a rudimentary setup. If you’re interested in further reading, we’ve covered the basics of X-ray crystallography before. We’ve also seen a few X-ray machines.