Looks like the Simpsons had it right again, now that an Australian radio station has been caught using an AI-generated DJ for their midday slot. Station CADA, a Sydney-based broadcaster that’s part of the Australian Radio Network, revealed that “Workdays with Thy” isn’t actually hosted by a person; rather, “Thy” is a generative AI text-to-speech system that has been on the air since November. An actual employee of the ARN finance department was used for Thy’s voice model and her headshot, which adds a bit to the creepy factor.

Deepfake6 Articles

Human Brains Can Tell Deepfake Voices From Real Ones

Although it’s generally accepted that synthesized voices which mimic real people’s voices (so-called ‘deepfakes’) can be pretty convincing, what does our brain really think of these mimicry attempts? To answer this question, researchers at the University of Zurich put a number of volunteers into fMRI scanners, allowing them to observe how their brains would react to real and a synthesized voices. The perhaps somewhat surprising finding is that the human brain shows differences in two brain regions depending on whether it’s hearing a real or fake voice, meaning that on some level we are aware of the fact that we are listening to a deepfake.

The detailed findings by [Claudia Roswandowitz] and colleagues are published in Communications Biology. For the study, 25 volunteers were asked to accept or reject the voice samples they heard as being natural or synthesized, as well as perform identity matching with the supposed speaker. The natural voices came from four male (German) speakers, whose voices were also used to train the synthesis model with. Not only did identity matching performance crater with the synthesized voices, the resulting fMRI scans showed very different brain activity depending on whether it was the natural or synthesized voice.

One of these regions was the auditory cortex, which clearly indicates that there were acoustic differences between the natural and fake voice, the other was the nucleus accumbens (NAcc). This part of the basal forebrain is involved in the cognitive processing of e.g. motivation, reward and reinforcement learning, which plays a key role in social, maternal and addictive behavior. Overall, the deepfake voices are characterized by acoustic imperfections, and do not elicit the same sense of recognition (and thus reward sensation) as natural voices do.

Until deepfake voices can be made much better, it would appear that we are still safe, for now.

EMO: Alibaba’s Diffusion Model-Based Talking Portrait Generator

Alibaba’s EMO (or Emote Portrait Alive) framework is a recent entry in a series of attempts to generate a talking head using existing audio (spoken word or vocal audio) and a reference portrait image as inputs. At its core it uses a diffusion model that is trained on 250 hours of video footage and over 150 million images. But unlike previous attempts, it adds what the researchers call a speed controller and a face region controller. These serve to stabilize the generated frames, along with an additional module to stop the diffusion model from outputting frames that feature a result too distinct from the reference image used as input.

In the related paper by [Linrui Tian] and colleagues a number of comparisons are shown between EMO and other frameworks, claiming significant improvements over these. A number of examples of talking and singing heads generated using this framework are provided by the researchers, which gives some idea of what are probably the ‘best case’ outputs. With some examples, like [Leslie Cheung Kwok Wing] singing ‘Unconditional‘ big glitches are obvious and there’s a definite mismatch between the vocal track and facial motions. Despite this, it’s quite impressive, especially with fairly realistic movement of the head including blinking of the eyes.

Meanwhile some seem extremely impressed, such as in a recent video by [Matthew Berman] on EMO where he states that Alibaba releasing this framework to the public might be ‘too dangerous’. The level-headed folks over at PetaPixel however also note the obvious visual imperfections that are a dead give-away for this kind of generative technology. Much like other diffusion model-based generators, it would seem that EMO is still very much stuck in the uncanny valley, with no clear path to becoming a real human yet.

Continue reading “EMO: Alibaba’s Diffusion Model-Based Talking Portrait Generator”

AI Camera Only Takes Nudes

One of the cringier aspects of AI as we know it today has been the proliferation of deepfake technology to make nude photos of anyone you want. What if you took away the abstraction and put the faker and subject in the same space? That’s the question the NUCA camera was designed to explore. [via 404 Media]

[Mathias Vef] and [Benedikt Groß] designed the NUCA camera “with the intention of critiquing the current trajectory of AI image generation.” The camera itself is a fairly unassuming device, a 3D-printed digital camera (19.5 × 6 × 1.5 cm) with a 37 mm lens. When the camera shutter button is pressed, a nude image is generated of the subject.

The final image is generated using a mixture of the picture taken of the subject, pose data, and facial landmarks. The photo is run through a classifier which identifies features such as age, gender, body type, etc. and then uses those to generate a text prompt for Stable Diffusion. The original face of the subject is then stitched onto the nude image and aligned with the estimated pose. Many of the sample images on the project’s website show the bias toward certain beauty ideals from AI datasets.

Looking for more ways to use AI with cameras? How about this one that uses GPS to imagine a scene instead. Prefer to keep AI out of your endeavors to invade personal space? How about building your own TSA body scanner?

Can You Remembrandt Where This Is From?

A group of researchers have built an algorithm for finding hidden connections in artwork.

The team, comprised of computer scientists from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and Microsoft, used paintings from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum to demonstrate these hidden connections, which link artwork that shares similar styles, such as Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion (above left) and Jan Asselijn’s The Threatened Swan (above right). They were initially inspired by the “Rembrandt and Velazquez” exhibition in the Rijksmuseum, which demonstrated similarities between the artists’ work despite the former hailing from the Protestant Netherlands and the latter from Catholic Spain.

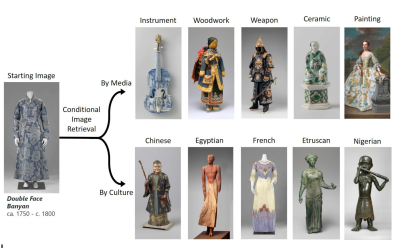

The algorithm, dubbed “MosAIc”, differs from probabilistic generative adversarial network (GAN)-based projects that generate artwork since it focuses on image retrieval instead. Rather than focusing solely on obvious factors such as color and style, the algorithm also tries to uncover meaning and theme. It does this by constructing a data structure called a conditional k-nearest neighbor (KNN) tree, which provides a tree-like structure where branches off a central image indicate similarity to the image. In order to query the data structure, these branches are followed until the closest match to an image in a dataset is found. In further iterations, it prunes unpromising branches in order to improve its time for new queries.

Some results from running the algorithm against museum collections were finding similarities between the Dutch Double Face Banyan and a Chinese ceramic figurine, traced to the flow of porcelain and iconography from the Chinese to the Dutch in the 16th to 20th centuries.

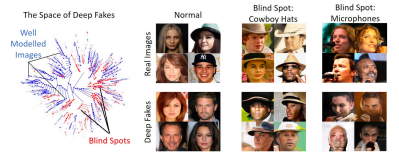

A surprising result of this study was discovering that the approach could also be applied to find problems with deep nerual networks, which are used for creating deepfakes. While GANs can often have blind spots in their models, struggling to recreate certain classes of photos, MosAIc was able to overcome these shortcomings and accurately reproduce realistic images.

While the team admits that their implementation isn’t the most optimized version of KNN, their main objective was to present a broad conditioning scheme that is simple but effective for applications. Their hope is to inspire related researchers to consider multi-disciplinary applications for algorithms.

This Week In Security: Simjacker, Microsoft Updates, Apple Vs Google, Audio DeepFakes, And NetCAT

We often think of SIM cards as simple data storage devices, but in reality a SIM card is a miniature Universal integrated circuit card, or smart card. Subscriber data isn’t a simple text string, but a program running on the smart cards tiny processor, acting as a hardware cryptographic token. The presence of this tiny processor in everyone’s cell phone was eventually put to use in the form of the Sim application ToolKit (STK), which allowed cell phone networks to add services to very basic cell phones, such as mobile banking and account management.

Legacy software running in a place most of us have forgotten about? Sounds like it’s ripe for exploitation. The researchers at Adaptive Mobile Security discovered that exploitation of SMS messages has been happening for quite some time. In an era of complicated and sophisticated attacks, Simjacker seems almost refreshingly simple. An execution environment included on many sim cards, the S@T Browser, can request data from the cell phone’s OS, and even send SMS messages. The attacker simply sends an SMS to this environment containing instructions to request the phones unique identifier and current GPS location, and send that information back in another SMS message.

It’s questionable whether there is actually an exploit here, as it seems the S@T Browser is just insecure by design. Either way, the fact that essentially anyone can track a cell phone simply by sending a special SMS message to that phone is quite a severe problem. Continue reading “This Week In Security: Simjacker, Microsoft Updates, Apple Vs Google, Audio DeepFakes, And NetCAT”