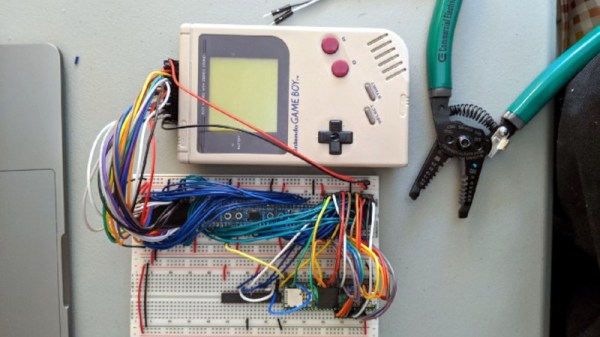

For those of us old enough to experience it first hand, the original Game Boy was pretty incredible, but did have one major downside: battery consumption. In the 90s rechargeable batteries weren’t common, which led to most of us playing our handhelds beside power outlets. Some modern takes on the classic Game Boy address these concerns with modern hardware, but this group from the Delft University of Technology and Northwestern has created a Game Boy clone that doesn’t need any batteries at all, even though it can play games indefinitely.

This build was a proof-of-concept for something called “intermittent computing” which allows a computer to remain in a state of processing limbo until it gets enough energy to perform the next computation. The Game Boy clone, fully compatible with the original Game Boy hardware, is equipped with many tiny solar panels which can harvest energy and is able to halt itself and store its state in nonvolatile memory if it detects that there isn’t enough energy available to continue. This means that Super Mario Land isn’t exactly playable, but other games that aren’t as action-packed can be enjoyed with very little impact in gameplay.

The researchers note that it’ll be a long time before their energy-aware platform becomes commonplace in devices and replaces batteries, but they do think that internet-connected devices that don’t need to be constantly running or powered up would be a good start. There are already some low-powered options available that can keep their displays active when everything else is off, so hopefully we will see even more energy-efficient options in the near future.

Thanks to [Sascho] for the tip!